ARMY AIR CORPS

Registered With Selective Service

Vancouver, Washington

June 30, 1942

Japan bombed Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, during my first year at the University of Washington. People sort of went crazy, especially college students. I recall that a bunch of them went snaking into and out of shops and movie houses along University Avenue one night. We were in a blackout at the time. The next summer the draft age was lowered to 20 years, which I attained that June. I had to report for a physical, which was really a quick look and a blood test, and I was qualified as 1A draft status.

Passed Test For Aviation Cadet Training

Portland, Oregon

September 22, 1942

I decided to enlist in the reserves and stretch my college education as long as possible. I took a test in Portland for the Army Air Corps (Cadets) and scored high in the written test but flunked the physical because my pulse rate would zoom too high. Then I took a test for the Navy Air Corps in Seattle. The examining doctor convinced me that a high pulse was strictly mental because of being excited. I passed the pulse test easily but flunked the eye test. They dilated my eyes and said I was far sighted and would need glasses in seven or eight years. (It actually took fifteen years). So then I marched back to Portland, calmly stuck out my wrist, and passed with a normal pulse. I was in the Enlisted Reserve Corps of the Army of the United States.

Back to college I went that fall and shortly thereafter received a notice that I had to report to the local Draft Board. I actually had permission from the Draft Board to enlist but the paper work had not caught up. I framed the notice on the wall. I don't have the notice anymore and always wondered what happened to it.

Start Active Duty

Portland, Oregon

March 26, 1943

The next Spring I received orders to report for active duty. I boarded a train in Portland, Oregon, along with many other college students from Oregon and Washington, and headed for Texas. This was my first big train trip other than one to Spokane, Washington for a high school music meet. The train headed up the Columbia River, through Idaho, Wyoming, and then south through Colorado and on into Texas. We stopped in Denver long enough to look around the city, a new and interesting place. The next morning we awoke in the flattest land I had ever seen, and golden with grain or grass. I think we were in northern Texas. We crossed the Red River and I was greatly disappointed. The river was practically dry but the dirt was sure red. Then on into Wichita Falls, Texas, and Sheppard Field.

Basic Training

Sheppard Field, Texas

March - April 1943

We arrived about March 29 and spent a month in Basic Training. Here we gave up our civilian clothes and suitcases for olive drab and suntan uniforms, and barracks bags. We had the usual Basic indoctrination. We already knew how to march and drill since we had all just come from college where ROTC was mandatory. But we marched and hiked anyway. When the wind blew it would raise clouds of red dust. In the morning one would find a line of red dust outlining ones body on the bottom sheet. One time it rained following a dust storm, and the streets became full to the curbing with red mud.

While we were here, I got together with another guy from Vancouver. Somehow we found out that we each were here, and we went to see another guy from Vancouver who we knew and who was in the hospital. They looked at us kind of funny when we got to the hospital. It turned out that something had happened to him and he was in Section 8, the mental ward.

We never did get a pass to town in the month we were here. But the drill sergeant upstairs would come back from many passes, probably a little drunk, and would proceed to wake us all up by skating up and down the upstairs barracks.

When we left Sheppard Field we were a mixed bunch. Half were from Oregon and Washington, and half were from Texas.

College Training

University of Minnesota

Minneapolis, Minnesota

May - July 1943

From Basic Training we entrained to the University of Minnesota for twelve weeks of College Training. This was part of our training even though many of us had some college before. When we got there it was still cold but when we left it was hot and humid. I had never been in such hot and humid weather and it really sapped my strength.

The trip north was again through interesting country that was new to me. The air smelled like grain or cereal, and the buildings were built out of stone. At the University we lived in the stadium. It was one big horseshoe shaped room under the seats of the football stadium. We ate in the large modern Student Union building. We marched everywhere we went, to chow and to classes. We developed a repertoire of college songs and a few army songs, which we would sing one after the other without stopping, everywhere we marched. One of the students didn't like some of our songs and wrote a nasty letter to the college paper. One of our officers decided to have a drum and bugle group to play at the evening formation. Since I had played the trumpet, I volunteered to play a bugle.

The math and physics courses were a snap since I had just completed five quarters in engineering at the U of W. Some of the guys struggled since they didn't have this background. However we also had courses like geography and speech, which were new and interesting, and plenty of physical training, or PT. Mom's sister Marjorie lived in Minneapolis and I visited her once before leaving the City. She had a good job with the telephone company.

Minneapolis had a lot of pretty lakes but they were also the home of lots of mosquitoes I found out. The city of St. Paul was next door and they called them the twin cities. The weather was often too hot and humid to really enjoy the place. We went to a bar one Saturday and I had my first alcoholic drink and I wasn't quite twenty-one. I think it was a gin and tonic with lots of ice, and it tasted good in that hot weather.

We were exposed to flying while we were there. We went to a small airfield north of Minneapolis and received ten hours instruction in Piper J-3s. The flight operator was Lysdale Flying Service. I didn't really get the hang of flying during this introductory period. First, one had to become accustomed to the engine noise and bumpy air, and then things became easier. One day a very fast moving, very dark weather front came through. I assumed that this might be the kind of weather that spawned tornadoes in the Midwest. I never did see a tornado.

Classification and Prefliqht

Santa Ana Army Air Base

Santa Ana, California

August - October 1943

From Minneapolis we took a long train ride all the way back to the West Coast, Southern California. I saw a lot of new country, especially across the hot arid states of New Mexico and Arizona. I saw Army units on maneuver in what I thought was God-forsaken country. I thought I would go over the hill (desert) if I was ever sent to a place like that. Finally we arrived in Santa Ana, California for Classification and Preflight Training. I guess this was the first time I saw smog. I do remember that the atmosphere was hazy or foggy as we got off the train, but it wasn't objectionable.

The first part of our stay at Santa Ana was called Classification. We were required to take all kinds of tests to determine our aptitudes. We were graded on our potential abilities as a pilot, navigator, or bombardier. At the end of these tests we had an interview with a shrink to test our mental outlook. They were noted for asking embarrassing questions. If one reacted or objected to their questions it was usually the end as a cadet. Most of the guys had them figured out and gave them satisfactory answers. A few didn't. In general, it seemed the point of our cadet training was to make life miserable to see if anyone would react. I determined not to react no matter what they threw at me, and with this attitude I made it through cadet training. After Classification, we were assigned to Preflight squadrons. I was originally in pilot Squadron 51, Class 44-E and was later switched to Squadron 64, Class 44-E. along with several others. Nobody remembers why the transfer. Class 44-E designated the year and the month we should graduate from Advanced Flight Training.

Santa Ana was a large base near the Pacific Ocean. We did a lot of marching and parading and PT. We also took classes. The classes I remember best were aircraft identification and Navy ship recognition, and how to take apart and reassemble guns. There were other technical classes that most of the guys struggled with but which were easy for me. The recognition classes were probably like speed-reading classes. We got so we could identify type and number of planes or ships when a slide was projected for just a fraction of a second. At Santa Ana, on a gunnery range down by the beach, I had my only try at firing a machine gun at a moving target. They could tell if you hit the target by colors left by the bullets. I don't think I hit the target once. We also fired Colt 45s, the only time I ever fired this gun, although we were issued one overseas. (The gunnery range at the beach is now probably all large, expensive homes. I'm not sure but I think the UC Irvine branch is located on the old base.)

We went on bivouac up in the hills east of Santa Ana. We marched for miles through orange groves to reach the place. We played army for a few days and then got a ride back to the base. As I recall we ran into a few tarantulas but nobody died. This wasn't the kind of army life I signed up for.

One foggy morning we went to nearby Newport Harbor for demonstrations on how to float using ones clothes to trap air. They then asked for volunteers to demonstrate life saving. I volunteered because I had taken life saving courses several times, for a few extra points. Later I received a certificate for having the second highest weighted average grade for all of the classes we took.

One weekend we went to Balboa and Newport. The weather was perfect. It was after Labor Day and all of the kids had left the beach. Nobody was on the beach. We went for a dip in the Pacific in just our shorts. On other weekends we would take the Red electric trains to Los Angeles, Long Beach, and Santa Monica. The train would go for miles through orange groves and truck gardens. Now, of course, the old trains are gone and the area is wall-to-wall houses, businesses, and freeways. They say that Standard Oil was instrumental in getting the old trains out so they could sell more gasoline. On reaching the station in Los Angeles, everybody would run to the Biltmore, or some other hotel to try to get a room. Of course they were all filled. We usually slept in the couches in the hallways. One time in Long Beach we were steered to a place where you could sleep for fifty cents. When we woke up in the morning and saw how dirty the place was, we got out quickly. I think it was called a flophouse.

Gigs were handed out whenever the Tactical Officers could find anything wrong and the penalty was walking tours on the weekend and carrying a rifle. One time I had to go on KP early and was of course not present when the rest of the cadets cleaned up the barracks and left for their daily schedule. When I returned I found that I had been gigged several times for dirt and lint in my area. I think a couple of my buddies did me in. Needless to say I couldn't leave the base that weekend because I had several hours of walking to work off. I was a little put out with the guys.

One time we were required to eat a square meal. We sat erect, faced straight ahead, and made mechanical movements with our arms to be able to eat. We also had some exotic meals. SOS, or chipped beef (sh..) on a shingle, and tongue were a few that I remember.

One weekend after getting to LA, we hired a cab to take us to Hollywood. I think the cabbie drove in a round-about way to get there to stretch his fare. We finally reached Hollywood and Vine and then set out to see the sights. The most interesting place was Earl Carroll's Zigfield Follies. This was in a large theater restaurant. We got in to see the show but had to stand up in back near the bar. It was really a spectacular show, the first I had seen like this, and they had audience participation. Some rotund Colonels would go up to stage and play bumpsy daisy with the dancing girls. Other noted places we saw were the USO, Brown Derby, Grauman's Chinese Theater, to name a few.

Primary Flight Training

Thunderbird Field #l

Glendale, Arizona

November 1943 - February 1944

From Santa Ana we entrained back to Arizona for Primary Flight Training. Thunderbird Field #l was run by Southwest Airways using civilian flight and ground school instructors. There was also a Thunderbird Field #2 located east of Scottsdale. Army Air Corps men were also stationed here for administration, such as Tactical Officers, Medics, Physical Trainers, and Check Pilots. By this time we were a little more mixed up. Besides Texans and guys from Oregon and Washington, our group included guys from Minnesota, Ohio, and other states.

Thunderbird was a nice place occupying a square mile of desert a few miles north of Glendale. Now this area is nearly wall-to-wall houses. In 1976 when I visited the field, the old airplane hangers, administration building, and living quarters were still occupying half the square mile. It is now used as a school for international relations and was originally founded by an ex-General.

The planes we flew were Stearman PT-17s, open cockpit biplanes. Being open it was necessary to wear fur-lined flight jackets, pants, and boots, since it was in the late Fall and Winter season and it was cold at flight altitude. The planes didn't have electric starters so it was necessary for one cadet to stand on the wing outside and insert a crank and crank up the engine or flywheel to get it rotating. Then the crank was removed and the pilot would engage the ignition switch to get the engine going. A cadet would then walk along the wingtip while the plane was being taxied out of the parking area to be sure of clearing the other planes.

My first instructor was named Frank Kunkel and he was an easygoing person. After just a few hours of instruction, he taxied to the edge of the field and got out and told me to take it around for a couple of landings. I will always remember the day. It was November 20, Mom's birthday. The first landings were generally not the smoothest, but they got better with time. In-flight instruction was given via a speaking tube connected to the helmet we wore. It wasn't the clearest communication but it had to do. Frank asked his students to come to his house in Phoenix after we had soloed. He took a picture of us, which I still have. Years later I found out that Frank lived in Ramona and visited with him in 1990 when we were on a trip to Mary and Jeff's.

On my first check ride with a civilian pilot, I got a very poor rating. Later on however, on a check ride with an Army Captain, I was given a very good rating. I think it was just the difference in personalities. However I did catch the flu and was shipped to nearby Luke Field. When I came back I was put back into Class 44-F and had another month to go. I stretched my remaining hours over this month and I think I improved a lot because of this stretch-out.

One day a cadet named Reuben Johnson told me that he had taken a plane up as high as it would go. I immediately decided to do the same thing on my next practice flight. I think I got up to 15,000 feet, at which altitude the controls were very sloppy. I could see for miles, especially snow-covered San Francisco Peak north of Flagstaff.

Several nights we were wakened by buzzing cadets from advanced flight schools. I don't know how they were able to get away from scheduled flights to seek out and find Thunderbird. We never had any free time at night in advanced flight training. The tower would try to put a spot light on them to get the number on the planes. I don't know if they succeeded.

One of the civilian flight instructors was Everett E. Johnson from Vancouver. I didn't know him but my family knew of him. One day I got to meet him and have a chat. I think he was married to a Vancouver girl named Pat Norwood.

One weekend I got together with Roy Higgins, a classmate from Vancouver. He was in advanced flight training at Luke Field, which was west of Glendale. I might have first made contact with him while I was at Luke Field with the flu. He wanted to see Thunderbird and came out to have lunch one weekend. And of course he had to pass along all the hairy tales about flying, whether they were true or not. One story was about losing several planes during a night navigation flight. I think these stories were largely not true.

Basic Flight Training

Marana Army Air Base

Marana, Arizona

February - April 1994

After primary flight training we took the bus to basic flight training at an airbase north of Tucson, Arizona. Marana Army Air Base was in the middle of the Saguaro cactus country. It was a large airbase and probably had several hundred BT-13 "Vultee Vibrators", basic trainers. There were several satellite fields spread out over the desert, which were also used.

The BT-13 was a low-wing, single-engine, fixed landing gear plane having about 350 horsepower. It was relatively east to fly although stories persisted that it would do such things as snap roll if one crossed controls when turning into the final approach for landing. After getting used to the plane in daylight flight, we were introduced into our first night flying. After a checkout we were on our own. This was the only time I saw a fatal accident during training. We were taking off and flying a pattern and landing at night. One of the cadets pancaked in at the end of the takeoff pattern and burned. I will always remember the red-hot shape of the plane, which we had to fly over that night.

I had one scary experience during daylight takeoff and landing practice. I had just landed and gave it the throttle to go around again. I forgot to neutralize the elevator trim tabs, which I had just used during the previous landing. This caused the plane to want to climb too steeply during takeoff. I realized what was wrong but instead of resetting the trim tabs or cutting the throttle to stop the takeoff, I instead pushed forward on the stick, which controls the elevators and held it until safely airborne. Pushing is just the opposite of the usual backward pull on the stick during takeoff. Altering the position of the trim tabs was something that a few instructors would do, reportedly to see how alert a cadet was. It is an unsafe practice to say the least.

I felt pretty good one day when the ground controller repeatedly asked all the planes to fly a shorter pattern when approaching for a landing instead of being spread out. So I did just that and landed directly in front of the controller with a perfect landing. He asked for the name and serial number of the cadet that had just landed. One day I took off and encountered a very severe and rapid turbulence in clear air. This was a new experience but is something that happens once in a while over the desert. One time after I had landed, my instructor told me that I had flown the landing pattern 1000 feet too high. I couldn't believe this and always wondered whether he just made up that story.

On one weekend several of us went to Tucson and went out to the University of Arizona. Nelson Eddy was giving a performance which we went to. But it wasn't the same as old Nelson, the Canadian Mounty, and Janette McDonald, whom I always enjoyed in the movies. So we left.

The barracks at Marana were one story, with three men to a room. One of my roommates, Kenneth Hull from Ohio, was always singing "Mairzeedotes and Dozeedotes and Lillamzeedivee...." It always bugged me until he finally slowed down. As you know, it is "Mares eat oats and does eat oats and little lambs eat ivy...."

After a night flight one could sleep in later the next morning. On one Saturday morning after a night flight, the other two cadets in our room had to clean up and stand inspection. It pleased me to be able to lay in the sack and pretend to be asleep when the tactical officer came into our room and made his inspection.

Advanced Flight Training

Williams Field, Chandler, Arizona

April -

August 1944

After completing basic flying, we bussed north to our advanced flying school, Williams Field. Williams was located east of Chandler, Arizona. It was nearer civilization and cultivation as compared to Marana in the desert. Here we flew AT-6 Texans, a low wing plane with retractable landing gear and about 650 HP. It was a very enjoyable plane to fly. The added horsepower made it easier to do acrobatics and to fly in general. There was a rumor that the relatively narrow landing gear made it prone to ground looping. I never found this to be the case.

Advanced flying was more of the same but in a hotter airplane. One day I took off with my instructor and a couple of other cadets, all in separate planes. I think we were headed for formation flying and some dog fighting. My plane shortly developed a red light, which was an indication of low oil pressure. I called the tower and departed from the rest of the group, and headed back to the field. Shortly the tower asked for my position. I told them that I was on the final approach and still had a red light. The engine didn't quit. It was probably a malfunction, but one has to play it safe.

On cross-country flights, all of which were in Southern Arizona, we usually took along some snacks such as an apple or two. On one such flight I dropped an apple to the bottom of the plane. It was easy to retrieve. I just rolled the plane to inverted flight and reached up (down) and picked it off the canopy.

My most interesting flight was a low level navigational flight. We were required to fly at 200 feet altitude to prevent buzzing. My destination was an airplane parked on an airstrip out in the desert near the Mexican border. We were told to fly over any hills, not around them. So I took off from Williams and cleared the small hills to the south and settled down to 200 feet. I hit Casa Grande right on time and was taken in by all the activity in the town below. From there on it was all out across the desert. There was a lot of turbulence, which caused the magnetic compass to bounce all over the place. I therefore relied on my gyro-compass because it did not bounce. When my estimated time of arrival was up, I didn't see a thing except the desert. So then I gained altitude in hopes I could spot my destination. I would see some dust blowing and thought that was caused by an airplane. I dove down to take a look but it was just dust, no airplane or airstrip. I finally realized that my "stable" gyro-compass had precessed about 40 degrees. I estimated that I might be 40 miles west of my destination. I finally called in and told my destination that I was returning to Williams. My call was acknowledged but I could hardly hear it. I obviously was several miles off course. Returning was no problem. I gained altitude, took a reverse heading, and soon was in the green and inhabited section of Arizona. It was a clear day and landmarks could be seen for miles, except over the desert. I missed flying at 200 feet on the way back. I explained my fiasco to my instructor and gave him a true assessment of what had happened. Nevertheless, on my next navigational flight, my instructor came along. He was always asking me, "Where are we now? What is that landmark down there to the left?" But I survived and finally graduated. The lesson: Don't rely on your gyro alone.

Another amusing flight was at night where we were practicing landings at one of our satellite fields. This satellite was a small triangular field in the desert. On call, we would come down from our holding position to shoot a few landings. One leg of the triangle would be illuminated for the landing and a control plane would be parked near the front of the strip to monitor the landings. After I was called down, made a landing, took off again, and entered the pattern for more landings, Control decided to change the direction of landing to another leg of the triangle. So I, and others, had to circle until the new leg was illuminated. And low and behold, the ultimate happened, something we always joked about. The first guy to land in the new pattern landed wheels up, he bellied in! So we circled again until they could establish landing on one of the other legs. Once we were on the ground, we had to taxi around the bellied-in plane. When the cadet was asked why he didn't put his gear down. The control plane could see the gear was up using their spotlight, and was warning him over the radio to pull up and go around. He answered with our ultimate joke. He couldn't hear the request over the radio because his horn was blowing too loud. The horn blows as a warning when the landing gear is not down and when the throttle has been retarded for landing! The guy wasn't washed out. This close to graduation they let him graduate. I later saw a picture of him in an Aviation magazine. He was a test pilot at Edwards AFB.

One day I noticed an inflamed lump and drainage on my tailbone. It was probably irritated from too many sit-ups on the hard desert floor. I reported to sickbay to have it checked out. The doctor said it was a pilonidal cyst. He told me to check into the hospital and he would remove it and have me back flying in a week. This I did. He said he would use a procedure to speed up the healing by sewing back a flap of skin rather than letting it heal from the bottom up. After one week it was still draining. I ask him how much longer it would take but he didn't know. I said I have missed my graduation class by now so why don't you give me a leave since there was no use hanging around the hospital. So I got a leave and went home to Vancouver. When I came back and resumed flying, I was now in Class 44G. I began to get boils on my fanny. I never had boils in my life and assumed it was the poison from the operation coming out. It was a little uncomfortable flying and sweating with big bandages on my fanny. Everything finally got back to normal.

To get home to Vancouver, I decided to fly. I went to Sky Harbor in Phoenix and caught a DC-3 to Burbank, which was the LA airport. At Burbank I was bumped because so many servicemen were returning from overseas and had priority. But I hung around and finally got a flight to San Francisco, arriving early in the morning. There I was bumped for good since there were so many servicemen returning to the States through San Francisco. After a quick nap I called Betty at Hamilton Field and she told me to come to Hamilton because Frank Nims was flying to Portland that afternoon. I caught a Greyhound bus and finally made it to Hamilton Field. Frank was taking a bomber to Moses Lake. He blew out a tire when landing in Portland and so stayed over night in Vancouver. I was a bit cold in the plane and was given a jacket by one of the crew. When I arrived in Portland I had dirt and grime all over my uniform. The jacket had obviously been used by a mechanic, and I think it was given to me to wear as a joke. Frank wondered how I got so dirty.

One of the plusses for making it into advanced flying was that mandatory physical training was eliminated during the last month and one could opt to go to the swimming pool. This was really nice, swimming and basking in the hot Arizona sun instead of sit-ups and other calisthenics. Another plus was going to the mess hall after night flying and being able to order a breakfast as you like it, such as bacon and eggs over easy. I was in line one morning and ran into Chuck Furno, another classmate from Vancouver. He was a class ahead of me.

We went to Phoenix to get fitted for our officer's uniforms. We ordered them to fit perfectly. I weighed about 145 pounds then. I still have the wool jacket, or coat, and when I put it on now, there is a several inch gap down the front. We were told not to order too many uniforms because we didn't know whether we would be shipped to the tropics or to cold country, and this was good advice. Graduation day finally came, August 4, 1944, two months after D-Day in Europe. We were given leave before our next assignment, so I went home to Vancouver again. This time I took the train all the way. Taking the train always meant a few hours delay in LA, before catching a train north. I took advantage of these few hours to see a small part of LA.

I was assigned to Randolph Field, Texas, for basic flight instructor's school. I took the train from Portland all the way to San Antonio, Texas, again via LA. Some of the graduates were assigned to advanced instructor's school. A few had volunteered for night fighter training. Most of them didn't get an assignment and were put into pools.

Basic Flight Instructor's School

Randolph Field

San Antonio, Texas

August - October 1944

Randolph Field was an old established air base. The buildings were all permanent types, made of concrete. This was a big change from the wooden barracks we usually had. And cockroaches galore! And at night there were thousands of fireflies lighting up the area.

Since this was basic flying, we went back to flying BT-13s, like we flew at Marana. The only thing that I can specifically remember that we learned was what to do if a student crossed his controls on the turn to final approach, and started to snap roll. At this low altitude there would be no time to stop the roll before hitting the ground. So we were instructed to take over the controls and complete the roll to get back to a right-side-up attitude. This maneuver took less time.

My instructor was a portly, somewhat gravelly guy and I don't think he liked me. But I showed him that I could do everything he could do and so I completed the course.

I had a practice routine wherein I maximized the number of maneuvers such as spins, stalls, loops, in the minimum amount of time. One observer student who rode with me thought I was wild. But I was just efficient with my time.

Temporary Duty

Gardner Field

Taft,

California

October 1944

After graduation from Randolph, we were assigned to Gardner Field and caught a train to Bakersfield, California. I had just been paid my first months pay as Second Lieutenant and it was in small denomination bills. Rather than carry this wad, I decided to put some in my B-4 bag. Someone in the depot must have seen me and several others do this because we got robbed. I lost about 200 dollars. Live and learn.

We finally got to Bakersfield and waited in the plush Bakersfield Inn for the bus to Taft. This was a cool, plush place, in the hot Bakersfield weather. I always wanted to see it again. Many years later, while visiting Robert in Bakersfield, I asked him to show me the Inn. It was now in the seedy part of Bakersfield and was all run down. I could hardly recognize it.

Gardner Field was a basic flying school and we were supposedly sent there to instruct. However, we never did instruct but instead received orders to report to Lubbuck, Texas, for advanced glider pilot training. Needless to say, I wasn't too happy about this. We took a train all the way back to Texas again.

Glider Pilot Training

South Plains AAB

Lubbuck, Texas

October - November 1944

Lubbuck is in the flat farming country of northwest Texas. It is also the home of Texas Tech. I and several hundred other power pilots from all over immediately started glider pilot training when we arrived. I continued for 11 days, 7 hours of flying, and 40 landings and was then rated a glider pilot. I guess they were expecting a big push in Europe and needed glider pilots in a hurry. Maybe someday I will find out the real reason.

Flying the CG-4A glider was easy. They had spoilers to cut lift, so one only had to come in higher than needed and then use spoilers as needed to land on a dime. The opposite maneuver, trying to stretch a glide was the wrong thing to do. It could be fatal.

We were towed aloft by a C-47, cut ourselves off from the tow plane, rather than have the tow plane cut us off, and proceeded to fly a pattern and make a landing. One day I was on a double tow where two gliders are towed by the same plane, one with a shorter rope than the other. We were taking off and had only gained a couple hundred feet altitude when the tow plane cut us off without warning. This is dangerous since the stretched nylon rope can come zooming right at you. The glider on the short rope then cut his towrope about a second before I cut mine. The rope didn't drop away or come crashing through my windshield, but it did slide past my left window. I thought, S.O.B., that rope will hang up on my left wing strut, which was behind me and out of view. I made an instant decision and used full spoilers and dived close to the ground as soon as possible. This was in case the other end of the rope caught on something on the ground and either ripped my left wing off or flipped me. My observer, another student yelled, "You are going too fast." I leveled off, clipping the tops of the cotton plants, until I slowed down, straight ahead and cross-furrows. The rope did hang up on the wing strut and did catch on something on the ground, after I was close to the ground. There was a big jerk and I was stopped cold. The rope had torn through the airfoil shape of the wing strut but there was a metal tube in the strut for strength, which held. I was so flustered that I left my A-2 leather flight jacket in the glider and that was the last I saw of it. That is the only "crash" landing I ever made. I never heard more about the landing. I'm sure I made the right decision and did things right.

We had about a week before we shipped out. I was shaving, preparing to go see Lubbuck that night, and who should be standing next to me doing the same thing but Herb Sugg, an old friend and neighbor from Vancouver. Herb had been a flight instructor at a field managed by his father in Klamath Falls, Oregon. He then joined the service and had just become a glider pilot. He was soon to get leave and go back to Vancouver and marry Gloria Kelso, his high school sweetheart. What a small world.

The last few days at Lubbuck were spent getting ready to go overseas. As requested, I had to send my camera home, but I immediately sent for it again after I reached my destination. We took a train ride again, this time to Camp Kilmer, New Jersey. The train took us through West Virginia where they mine and burn a lot of coal. At one station stop, I got out to walk around and found a half-inch layer of black coal dust or ash covering the railings. I wondered how people lived in this grime. And yet the trees were green and growing.

Overseas Preparation

Camp Kilmer

New

Jersey

November 1944

Camp Kilmer was not too far from New York City. Before we departed, several of us commuted to the big city one night, to see the famous sites. We visited, for the first time of course, the top of the Empire State Building, and Rockefeller Center. At the Center we were able to see the Rockettes perform. Outside the Center there was an ice rink with skaters. I'm sure we saw many other places which have dropped from my memory.

At the camp, we continued to get ready for shipping out. Then one night we boarded a ferry which took us to our troop ship in New York. It was the Aquatania, a sister ship of the ill- fated Lusitania. The ship left port in the middle of the night so I didn't get to see any of the harbor.

Aquatania

Atlantic Ocean

New York

City to Greenock, Scotland

November 15 - 23, 1944

The Aquatania held about 8,000 troops. We slept in cots which were three deep. After we were underway, I was assigned an armed guard at night to patrol a designated section of the ship topside. We had to be sure that nobody was lighting up or signaling in any way. After we completed our tour, I got to climb up to the bridge to report everything was OK. This was very interesting.

The ship was unescorted for the first few days. We zigged and zagged all the across to keep from being torpedoed. The weather was clear most of the way over. We could see porpoises keeping up with us in front of the ship. The weather turned foggy, probably as we were nearer to land. Then I noticed a small destroyer, or some type of naval ship, would come in close enough to be seen, send signals to our ship, and then disappear again in the fog. We were all required to go topside one day, to get fresh air I guess.

The British crew was very cockney. They would try to teach us the British monetary system with their very cockney accent. It was like trying to learn a foreign language. Thrupney bits and so on. I never did catch on.

Finally, one morning, we found ourselves in a very large harbor, Greenock, Scotland. I watched as they unloaded our ship onto smaller ships or barges. Sometimes they would drop a load into the water. Someone didn't get their footlocker and bags. When we were taken ashore, a lady was handing out tea or coffee and some tasties. To me she looked exactly like Bill Paeth's mother and she was Scottish. I almost told her this but I knew it wouldn't mean anything to her. The Paeths lived just outside Vancouver.

From Greenock we boarded the British railway system. We went, totally blacked out at night, through some very wet and green countryside, until we came to our destination in England.

Replacement Depot

England

November

1944

I never found out exactly where in England this Replacement Depot was located. We didn't stay there long but were quickly separated and dispersed to one of several airbases in England. While we were at the depot, we had at least one mail call. A guy standing next to me yelled out, "Get Hogg's mail," to someone standing closer to the guy handing out mail. The guy was a B-26 bomber pilot named Hogg. I thought somebody was trying to steal my mail. The mail must have been forwarded from the states.

Leaving the depot for our assigned air base, our train stopped at Coventry long enough for us to walk into town to get a bite to eat. Coventry was one of the English cities the Germans had bombed heavily, nearly wiping it out. We found a cafeteria, walked in, and ordered. I was, I guess, not expecting the menu which was offered. We got a very small sliver of boiled meat along with lots of potatoes and greens. There was a big sign saying that seconds on greens could be had. At that time I wasn't in the mood. We found out that good food was hard to get.

Back on the train, we finally reached a station near our assigned airbase and were picked up by trucks for a ride up the hill.

310th Troop Carrier Squadron

315th Troop Carrier Group

9th Air Force

AAF Station 493

Spanhoe, England

November 26, 1944 - April 11, 1945

Spanhoe was a Troop Carrier Base located north of Kettering and east of Leicester, two good sized cities. There were smaller, closer towns in this country called the Midlands. Troop Carrier was the outfit that dropped paratroopers, towed gliders, made supply missions, carried out wounded and liberated personnel, and carried fuel to fields near the front line of action. Some planes from our group carried Glenn Miller's band to Paris in December. Miller was lost flying with some Colonel in a single engine plane.

|

We were taken to an unoccupied Quanset hut away from most of the other huts. It was cold, and the only heat was from one very small English design coal-burning heater. It was all one could do to keep a coal fire going because it was so small. I got out of my pad one morning and tried to get the fire going. A smart-ass, know-it-all pilot named Goering (just like Herman the German) stayed in his pad and proceeded to tell me how to do it. I was mad as hell and just about upended his cot, to make him get up and show me how to do it. I never liked the guy.

After a couple of days of more-or-less isolation, nobody appeared to care that we were there, we went to our Squadron Commander, Lt. Col. Hamby, and requested that we be allowed to fly. Since we were pilots with ratings of 1- engine and 0-engine, we would have to receive instruction in the 2-engine C-47s of Troop Carrier. It appeared that there was no real need for glider pilots, at least in the immediate future, and they already had many regular glider pilots. First we were split up to live among the old-timers in the squadron. Then we did receive instruction in the C-47 and got to ride as copilots on the supply missions they were making. At first I found that just taxiing the C-47 was difficult. Then I moved my seat back so that my feet weren't bent up on the rudder pedals. This relieved the tenseness and made taxiing easier. Once airborne, the plane was easy to fly. I never did find out how to make a smooth landing in a C-47.

Most of the old-timers in the group had flown over to England in 1942 and 1943. They flew by way of Labrador, Greenland, and Iceland. From England they flew to Africa and participated in that war before returning to England in early 1944. All of this history is included in a book written by one of the old-timers, W.L. Brinson. It is entitled, "Three One Five Group." I have a copy of this book. From England they participated in D-Day Operation Overlord. They took off from Spanhoe just before midnight on June 5, 1944 and headed for France to drop paratroopers. The next big mission was Operation Market Garden in which airborne forces were flown into the Arnhem-Nijmegan area of Holland in September 1944. Since I arrived in November, this was all in the past. Most of our flights were supply missions.

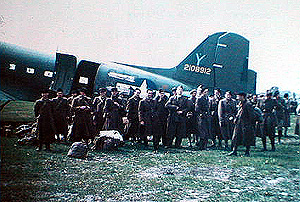

Spanahoe, England April 1945 |

Not until March 1945 did another big airborne mission take place. This was named Varsity and its mission was to facilitate the Rhine River crossing in the area of Wesel, Germany. For this mission, crews of the 315th moved closer to the English Channel, to a field called Borham, northeast of London. I flew down with Lt. Drummey. We were briefed for the mission but Drummey and I were one of two alternate crews and did not go on the mission. Instead, we flew back to Spanhoe to await the results of the mission. While waiting the results, I was notified to pack my bag for shipping to another air base. I presumed I was to fly a glider. Well, it never came to pass and I was relieved. I did know a guy in a different group who did fly a glider on this mission. Although the whole operation was a success, it was very costly. Our Group Commander Col. Lyons and his crew were shot up but managed to bail out. They were taken prisoner but were rescued a few days later by the same British paratroopers they had dropped several days before. Some were killed and some were missing in action for a few days. Lt. Berman of our hut came back six days later and was mad as hell at his buddies who were already divvying up his belongings. Total damage to the group planes was 19 of 81 destroyed or beyond repair and 36 others damaged.

Spanahoe, England December, 1944 |

In December, the weather was very cold and very bad, and we did not fly often. We did listen to the German propaganda on the radio. A few of our personnel had been sent to Pathfinder, a unit that had better navigation aids. One of these was a navigator, Frank Hayden. I met him at the University of Washington after the war. They were on a mission to the Battle of the Bulge, in miserable weather. His plane was shot down and he was captured by the Germans. He described his walk back to a prison camp in detail. He said they were liberated by the Russians. A Russian General decided that they needed food and they rounded up some cows for them. He said the prisoners sort of went crazy milking, killing, and butchering the cows.

On Christmas day, I walked off the base on a road through the King's forest. I was about to take a picture of the trees all covered with a thick coat of ice when along came a Brit on a bike. As I snapped the picture, he pedaled by and said, "Well, well, Bing Crosby's White Christmas, 'haint it?"

After being in the group for a while, several of us got passes and went to London. This was very interesting. We toured all over London. We saw the changing of the guard at Buckingham Palace and they weren't in bright red uniforms, but were in army olive drab. We saw where the Germans had bombed and yet much was still standing. We ate in a huge establishment where they served food to officers, Grosvener House. We stayed in small hotels which were run by the Red Cross. And yes, we saw the Picadilly Commandos, plying their trade. There were no more V-l buzz bombs but V-2 rocket bombs struck here and there in England. They were not very accurate. A few hit London.

Spanahoe, England 1945 |

There was an airbase about every five miles in any direction, all over England. Most of these were bomber bases. The B-17s would take off early in the morning from several bases, and form in to groups, flying back and forth. At Spanhoe we could see the formations overhead. They usually left vapor trails and the sky would become totally clouded by these vapor trails before the groups would leave England for the continent. The English did their bombing by night and would take off late in the day. One time heading back to Spanhoe above the clouds, we were headed right at some big Lancaster bombers, grinding up and breaking through the clouds. It was a good thing we were not skimming close to the clouds or we could have collided. We heard bombing one night. It was reported that a German bomber had followed the British bombers back to their base at night without being detected, and dropped a few bombs. We flew into Croydon, a London airfield. Croydon was entirely circled by brick houses, like it was in the middle of the city. We couldn't return to Spanhoe on one trip and sat down at a base on the south side of the Thames River, east of London and near a town called Gravesend. They put us up in a hotel for the night. The view from the tide flats by the river looked exactly like the scenes they made in the movie called Great Expectations.

|

|

1945 |

We were non-operational one day but could take planes up to maintain proficiency. Lt. Bob Sutton, an old-timer, asked me about a P-51 pilot friend of mine that I had mentioned. The friend was Lt. Roy Higgins, a classmate from Vancouver. We also went to the University and worked at Alcoa together. Dad had sent me the number of his fighter group and Lt. Sutton was able to locate the field through communication channels that I was not aware of. He had Roy notified and we flew the short distance to the field near Cambridge where Roy was waiting at the control tower. The first thing he said was, "Well I see they finally got you over here." We took him for a flyover of Spanhoe and back. Then Sutton requested permission for a fighter approach, which was granted. We went full throttle down to the deck and then pulled up into the tightest 360-degree loop pattern that I had ever been in. I thought we were going to fall out of it at the top when all G's disappeared. But I managed to get the gear and flaps down, and Sutton pulled it around and down and made a perfect landing. He got an accolade from the tower. He wouldn't have been allowed to do this at Spanhoe and I think this was his reason all along for wanting to go there.

After we landed, Roy suggested that we meet in London. He would make all arrangements for staying in London. I agreed and went to London on the agreed upon day. Roy didn't show up. I spent a couple of days looking around, then returned to Spanhoe. Later I received word from home that Roy had been killed in action. He had been on his second tour of duty. After I came home I visited Roy's father. He had received copies of Roy's gun camera films, all edited and titled with dates and names of his missions, shooting up the Germans.

I think it was in December when the Group decided to have a party. Everybody was allotted two bottles of champagne, but I decided that I wasn't going to go. I was harassed by Lt. Sutton to go up to the club and get my champagne. Finally I relented and came back with the champagne. Sutton said, "Now you have to catch up with us." He poured a canteen cup for me. I had never tasted champagne in my life. I took a sip and it tasted pretty good, and then took a big drink. All of a sudden I had this sick feeling in my stomach and raced for the door. I got about half way to the door when all of a sudden it came up. It was all gas, the biggest burp I had ever had. What a relief! That wasn't so bad, and then I had some more. We went to the club and I ordered some scotch. I never had scotch in my life. I could see that it was tapped from a small keg that looked like it was creosoted. And that is what the scotch tasted like. I didn't like it but that is just the way scotch tastes. I soon had too much and went back to my pad.

On one trip to France we stayed at a Chalet. We were told that the crapper was out of order but that we could use the bidet, but be careful what handle you pull! This Chalet had been used by the Germans. In the basement were all kinds of German technical manuals. These manuals were very well made. They had transparent plastic pages, each with a picture of part of the machinery. Turning the pages was just like disassembling the machinery. I collected several of these manuals and put them in my footlocker. My footlocker was later stolen when it was shipped to Puerto Rico. They would have been great souvenirs.

On another trip to France, we took supplies to a field at Chartres. We had time to ride into town and see the historic Chartres Cathedral. Very Beautiful. But it was an old city and had the smell of sewage running down the gutters of some of the streets.

Amiens-Glisy, France

April 11 - May 8,

1945

Mine is second from the right. April, 1945 |

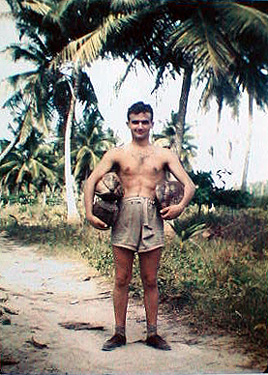

To get closer to the action, we picked up and moved to this airbase near Amiens. We lived in tents. April was a very warm month and there was a reservoir a few miles from the field where we went for a swim. Later we were told that it was contaminated so we didn't swim anymore. I have a color slide showing several of the guys basking in the nude. Lt. MacGregor and I went for a hike off the base in just our shorts and shoes. We walked to a small village called Bove where we saw an old farmer herding a flock of sheep through town. I have an excellent color slide of this scene. Out of the village we climbed a small hill toward some ruins. I don't know what the ruins were. On the hill was an old woman gleening twigs and putting them in a sack. She probably got her fuel this way.

Once we went into a French town and decided we needed a bath. We entered Bains Douche? and were escorted to a room with a bath and elegant plumbing. I had to go to the bathroom and asked directions. They pointed down the end of a hall but I couldn't find it. I finally went just outside and found it in a lath cubical. There was a water tank on the wall and a sloping floor with a hole centered in it. That was it. And yet they had all the inside plumbing for the bath. I couldn't speak French but finally ask the female attendant to leave so I could take my bath. Maybe she would have stayed and scrubbed my back.

One time Lt. Ken Hilburn and I went into Amiens to get a haircut. Ken got his cut first. When he was finished he said, "When he asks you something, nod your head yes." At the end of my haircut I nodded. The barber proceeded to pour a lot perfumey, stinging tonic on my head. I smelled like a you-know-what for several days.

We made many trips into Germany in the final days of the war. The German air force had been mostly done in, although there was an occasional wild one that would try to reek as much havoc as possible. There were many pockets or islands where the Germans still existed. We knew where these were and avoided them. On one trip where we hauled fuel, I saw a C-47, at the end of the grass field, tilted like it had a flat tire. As we rolled past, I saw that it was riddled with bullet holes, probably as it was landing or taking off.

Brussels, Belgium, 1945 |

On another trip to Germany, we brought back a load of liberated officers. They had been prisoners for five years but didn't look very bad off. I think they had been used as workers. Anyway, they looked very happy to be flying out. I showed them where we were on the map and they were very interested. They were also interested in the names of the various aircraft that they saw at Brussels where we landed. I took a color slide of them beside our plane. They gave me a note of appreciation, which they all signed. I have always wondered what happened to that note.

Once we carried some walking wounded back to Paris. We arrived at Le Bourget field shortly after dark and had to radio the British, who ran the field, to turn on some landing lights. They said they were closed but eventually did give us some lights. The English were probably having their tea, or something stronger. Some of the guys went into town that night. I didn't go but wished that I had gone. They described some very quaint places. Most of the crews slept on the ground. I decided to sleep on a stretcher in the plane. It was the coldest night I ever spent. Sleeping on the ground would have been better. We always carried sleeping bags with us for such occasions. Le Bourget was where Lindbergh landed.

April 1945 |

The next day we took off and circled the Eiffel Tower at very close range and then landed at Orly field. I had time to run into Paris to see the Arc De Triomphe and the Eiffel Tower from the ground.

Many of our trips were for hauling fuel, 100 5-gallon jerry cans being a full load. The capacity of the fuel tanks in the plane was 800 gallons. We probably burned up 500 gallons on a trip to deliver 500 gallons in cans. But we delivered the fuel to small fields or strips where it was needed. The fields were generally grass, which had been covered with straw and perforated steel matting to make a runway. The taxi perimeter didn't have this matting and quickly became several inches of mud, which required a lot of power just to taxi. But Troop Carrier had about 1,500 C-47s, and it was possible to put 1000 planes into the fields each day. We could deliver 500,000 gallons of fuel a day close to where it was needed. I guess they couldn't build pipelines fast enough to keep up with the advancing armies. Each squadron also had a C-109 air tanker, which was like a B-24 with a 3000-gallon cabin tank. These were never used since they couldn't get into small fields. After the trips, when the planes were empty, we would usually buzz the countryside all the way home.

On another trip to Germany, we landed at what had been a major airport. The huge hangers had signs saying, "Rauchen Verboten," or No Smoking. There was a wrecked ME-109 on the field, from which souvenir hunters had taken pieces. I couldn't find anything to take. One of the GIs stationed at the field was trying to sell new German Braun radios, which they had captured from some warehouse. The radios were each missing one tube however, and wouldn't work. But my radio operator and I each bought one for twenty bucks. My radio operator found a shop in a village near our field at Amiens, which had the missing tube equivalent. With the tube, the radio was really great. It could pick up short wave as well as regular broadcasts and had great tone. I carried the radio with me to the Caribbean and later to Seattle, when I returned to the University. The radio went out once in Seattle and my brother Lad, who was an amateur radio buff, fixed it so it played again. I enjoyed it for several years. In Puerto Rico however, it was almost too much listening to their brand of Latin music and the news in Spanish. When we first entered Puerto Rico, the customs agents tried to take the radio away but I hauled on one side of the counter while they hauled on the other side, and I won. Later, guys with souvenirs like this had them confiscated and had to get a letter from their commanding officer to get them back. I'm sure the Puerto Ricans would liked to have kept them.

We went into Germany once to pick up some infantry officers and take them to the Riviera for R&R. We were late arriving because of the weather and had to wait for them to return to the field. At the field was an Army tent hospital. The Major in charge gave us a tour of the hospital. He showed us some old, liberated, displaced persons who had gone to town in Germany and been fed wood alcohol. Some had already died and some were heaving their last as we walked through. We told the Major that we were scheduled to return to that field with other personnel that day. He asked for a ride and we took him and his nurse with us. However the storm was still over the Alps and the cloud cover was too low to risk a direct flight so we turned to the West and ended up in Paris. Our navigator, F/0 William Watts, and I went to see the sights of Paris that night. The next day we reached the Riviera but had engine trouble and couldn't return to Germany. We stayed in the Carlton Hotel at Cannes that night. The hotel was entirely taken over by the military. I saw the Major and his nurse walking around that night and don't know how they got back to Germany. F/0 Watts was from California but entered the U of W after the war.

It was nice weather in Cannes and I went into the hotel to rent a swimsuit to go to the beach. The French girl in charge of suits started complaining in English about, "Why is it always you and never us." I got mad and said, " I didn't ask to come over here and I would be damned glad to get home." When we went to the dining room that evening, the Matre'd, a very tall man, looked down on us and said that we could bring female guests to dinner. We left and walked around the block but didn't see any femmes, and so returned to the dining room. Maybe I missed something.

On this trip there was a P-38 fighter that had landed too fast on the short field at Nice, and collapsed the nose wheel. It was sitting at the end of the runway. I later learned that it was flown by General Quesada, head of the 9th Air Force. We saw him in the hotel that night living it up. Quesada later became head of the FAA. I have a color slide of the P-38 and always thought I should have sent him a print while he was in the FAA.

Munich, Germany May 6, 1945 |

The last and longest flight we made into Germany was to a field near Munich. It was a day or two before the end of the war. Coming into the airfield there were two fields of humanity below. One field was a gray color and consisted of captured German army soldiers. The other field contained liberated prisoners, waiting to be flown out. Our passengers were some very tall Indian Sikhs that had been part of the British army and had been captured in Africa. They wore tall turbans and still had their whiskers, and looked fierce. We hauled them to a field at Riems, France. At Reims, there were two identified C-47s on the field. One belonged to Air Marshall Tedder, and the other belonged to Eisenhower. I don't know if the two were there, but their representatives were there. I later learned that they were signing the surrender by the Germans. VE Day was a day or two later.

Flight to Trinidad

May 8, 1945

When VE Day arrived, everybody started to celebrate. Flares were being shot off like mad. Everybody was elated. Planes were buzzing around. I was notified to pack my bags because I would be leaving the next day. Our group was assigned to the "Green Project" in the Caribbean. A few of us flew out on a C-54 transport the day after VE Day. The old-timers later flew out in our C-47s fitted with an extra fuel tank in the cabin. The rest of the group shipped out by boat.

I packed in a hurry, taking only one bag and a burp gun. I put my Colt 45 pistol in my footlocker for shipment. We didn't have time to check in our armament. A C-54 arrived the next morning and we took off for Africa. We left France by way of Marseille and crossed the Mediterranean to Oran, Algeria. We avoided Spain and the Baleric Islands. I wondered what Franco would do if we had to land there. Little did I know that many downed fliers were slipped into Spain by the French underground, from where they were repatriated. From Oran we went to Casablanca and stayed overnight. We had time to see Casablanca and the thing I remember was the stinking sewers in the streets. We then flew to Dakar. The thing I remember here was how jet black the natives were. We then flew across the Atlantic at night. This was the first time I crossed the equator. I think we were sprinkled with water to initiate us in the realm of Jupiter Rex. We landed at Natal, Brazil. The country reminded me of Arizona, the climate and the flora. We had time to go to the beach and take a swim. The Brazilians on the base tried to sell Chanel No. 5 perfume. I bought a bottle but never knew whether it was the real Chanel. They also sold boots. I was always envious of those who had come this way to Europe and had Belem boots even though they were strictly non- uniform. I bought a pair but later found that I had picked a pair that were too small. They were uncomfortable. I still have them and the kids have worn them.

From Natal we flew in a C-46 Commando to Belem, Brazil, where we stopped briefly. I could see the wide outlets of the Amazon as we flew in. Then we went on to Trinidad, an island off the coast of Venezuela. We stayed at Trinidad a couple of weeks until the old-timers arrived in the C-47s. Then we moved up to Puerto Rico.

Air Transport Command "Green Project"

Waller Field, Trinidad

May 12 - 27, 1945

Borinquen Field, Puerto Rico

May 27 -

September 26, 1945

May - Sept. 1945 |

The Green Project was reported to be the biggest mass troop air movement in history. Most of the troops were moved from Italy to Casablanca by 15th Air Force tactical aircraft converted to troop carriers. ATC C-54s then shuttled the troops to the United States via the Azores and Newfoundland, and also to Natal, Brazil. From Brazil, former Troop Carrier C-47s were used to fly to Miami via Belem, British Guyana, and Puerto Rico. Our Group which was now part of the Air Transport Command, was assigned the last lap, the run between British Guyana and Miami. We were stationed midway between at Borinquen Field, Puerto Rico. Borinquen was at the extreme northwest corner of the island, at an elevation of 200 feet. Waller Field in Trinidad was turned into a huge maintenance base. Atkinson Field in British Guyana, our southern terminus, was located in the middle of a jungle, several miles inland from Georgetown. The full movement was to bring 50,000 men a month to the United States of which 20,000 a month were to be sent through our operation. With each C-47 holding 20 passengers, this required a takeoff or landing every 25 minutes at Puerto Rico. The objective of the whole operation was to redeploy the troops as fast as possible since the war with Japan was still going. All of our orders described this as an emergency war mission.

When we started flying the Green Project, it was probably like flying a scheduled airline, day and night. The old-timers got the Miami run while we newer ones had to take the southern run to Atkinson Field. I was assigned to fly with Lt. Bill Schilling who was from New York. We would fly to Trinidad and leave the plane for maintenance and stay overnight. Then we would go south to Atkinson Field and stay overnight. The next flight would be back to Borinquen with 20 passengers and without stopping. Once, in Trinidad, a few of the base personnel wanted to go to Tobago, an island northeast of Trinidad. So we flew them over there for a swim. The beaches of Tobago were of the whitest sand I had ever seen. Another time, after leaving Atkinson Field at night, we ran into the roughest storm I had ever encountered. The lightning would strike and light up a big thunderhead, which we would try to dodge. But the up and down drafts were very potent. First it was full throttle to try and maintain altitude in a big downdraft followed by reduced throttle to keep from gaining altitude on a big updraft. Finally the storm subsided. We could see the cloud remnants of the storm back-lighted by the rising sun. Needless to say, the passengers were all sick. They usually got sick whether it was rough or not.

On a night trip down to Trinidad I was given strong winds from the east so I calculated a correction to our course. When the ETA was up, our radio compass showed Trinidad to be due west. So we flew west a few miles until we got to Trinidad. The course correction was obviously too much to be so far east. But with the radio compass it was easy to locate where we should be. We landed in a very heavy downpour, the heaviest rain I had ever been in during a landing. After checking in, we were taken to our barracks for an overnight stay. After arriving, I heard a jeep speeding along the road out side, and then the sound disappeared. We went outside and saw a jeep upside-down in a ditch that was filled with water. We reported the accident but they couldn't find any body under the jeep after lifting it up. Evidently the driver had been thrown clear before the jeep ended up in the ditch, and took off.

We went swimming one night in the Gulf of Paria on the west coast of the island. The water fluoresced a bright yellow when it was disturbed, and left this colored trail a few feet behind. One night we went to the Navy Officers Club on a point of land west of Port of Spain, the biggest city on the island. This was a very beautiful place. I thought of the calypso song "Go down point Cumana," but this was another place. There was a giant turtle on the beach for some reason, the biggest I had ever seen.

At Atkinson Field, we were sitting around the club one night listening to Lt. Irving Sternoff sing, accompanied by a pianist. Jake was a trained operatic singer and was terrific. He was from Seattle. And then I heard somebody shout, "Hey Spence." It was Lt. Charles Stetcher, a classmate from Vancouver. He was flying a plane home from Europe. We had a long chat.

We always expected the planes we flew to be in top condition. If we found anything wrong or suspect, we would return it for a different plane. Crew chiefs didn't fly with the plane like they did when we were in Troop Carrier and the maintenance didn't seem to be as good. We decided our plane was a little rough on a night flight north of Trinidad and made a stop at St. Lucia Island rather than continue to Puerto Rico. This was a pretty palm-studded island. The buildings were on stilts, probably to prevent flooding during a hurricane. And the club had a good selection of calypso records. I later thought I should have made a collection of these records.

Switching gas tanks was always an experience, especially at night. Each tank was supposed to be settled and drained of any water, through a spigot under the wing. One was supposed to feel whether the draining liquid was water or gasoline. I was never sure which was which, but this was not my job. Invariably there would be some water remaining, which made the engines sputter for a few moments until it was used up. Takeoff was always done using gasoline feeding through a standpipe in the tank, to be sure no water got to the engine during this crucial period. Later the tanks could be used up by switching to the bottom outlets. At night, at 10,000 feet over the ocean, pitch black, no field within sight, tanks were switched, and the engines sputtered for a while, and your heart rate went up for awhile, but everything worked out all right, we made it. Some planes used up more gasoline than others even though they were supposed to be at the same engine settings. Of course wind direction also figured into gasoline consumption per mile. On a trip to Miami one night, after we got to fly the northern route, gasoline consumption was higher than normal so we stopped at Nassau in the Bahamas, before we got to Miami. We didn't leave the plane so we didn't see anything new, even at night.

Flying from Waller to Atkinson in the daytime we could see where the Orinoco river emptied into the Ocean. The river effluent was very muddy and brown. It carried out into the ocean a few miles and then dumped the silt. There was a very marked line where the brown changed to blue. As we reached British Guyana, we cut in over the jungles. Atkinson was surrounded by jungle and a very deep perimeter ditch. Once it rained so hard in one hour that the ditch became full to the brim like a running river. I always wanted to lay over at Atkinson and catch a ride to Jimmy Angel Falls in Venezuela, but I never got the chance.

At Borinquen they had rules that developed photographs were supposed to be inspected locally. I had several roles of Kodachrome, which I didn't want confiscated. I mailed them to Rochester, N.Y. for developing and gave my home in Vancouver as the return address. This worked perfectly, but I had to wait a few months until I got home, to see how they turned out. Most of these were slides taken in France and Germany.

We finally got to go on the Miami run and this was a welcome treat. This run was the longest by far. It was 1003 nautical miles, or about 1100 statute miles nonstop. It required careful watch of fuel consumption to be able to make it. It was all over water. There were radio checkpoints along the way in the low-lying Bahama Islands to the north. A hurricane once halted flying for about a week. It started just north of Puerto Rico and then went straight for Miami. We asked the personnel at the radio check points how they made out since they were only a few feet above sea level. At Miami we could see where the storm battered the palm trees. This run is actually one leg of the Bermuda Triangle but we didn't run into any mysterious happenings such as disappearing planes. One night a crew was returning from Miami and requested permission to land, which was granted. But the plane never landed. My roommate was in the tower that night and saw flares coming up from behind the cliff. Borinquen sits 200 feet above the ocean. Evidently the crew didn't have their altimeter set correctly and flew the base leg of the pattern too low, right into the drink. The plane sheared off the landing gear when it first hit and then settled smoothly into the water. The crew was able to open the door and inflate a raft, and safely escape. They had a hearing but didn't receive any discipline. The examiners thought the crew was just lucky to escape. I don't understand how it happened because below 200 feet altitude the field lights would have disappeared, giving time for recovery before crashing. Maybe they were too sleepy.

There were no facilities for overnight stays at Miami so we stayed at hotels at Miami Beach. Hotels with swimming pools lined the beach. What a change! I guess it was off-season for the New York crowd since there were always rooms available. One night a few of us took a taxi to a big nightclub or dancehall. Above the marquee at the entrance was a huge sign like on a movie house. The sign gave the name of the all-girl orchestra that was playing and said, "Featuring Norma Carson, the World's Greatest Cornet Player," or words to that effect. I thought there could only be one Norma Carson on the cornet, and she played in the Vancouver High School Band, as did her sister Ruth. Sure enough, it was the same Norma. I went up and talked to her during an intermission and she introduced me to a couple other girls in the band who were from Vancouver. One was red-haired Bonnie Adleman, on the bass, and I can't remember who the other girl was. We had a long chat. I always wanted the opportunity to go see her again but never had the chance.

One night, on returning from Miami to Borinquen in September, the Japanese surrendered. We missed all the celebration that went on back at Miami. Instead we purred along at 10 or 11,000 feet altitude, totally dark, over the ocean, and listened to the festivities on the radio. We were going in the wrong direction. Shortly after V-J Day, our operations folded up and I was soon to be sent home.

While at Borinquen, a group of us decided to go to San Juan. We hired a cab and rode along the north side of the island for many miles. After we got to San Juan we went to a hotel bar for some refreshments. An inebriated girl came over by our table saying that she had been left by some guy, and was quite unhappy. Later I called the Navy Base to locate Ensign Bill McLaughlin, a classmate from Vancouver, who was a Navy pilot. I had learned that he was here from a letter from home. I located him and he came down town to meet me. We went to a sort of disco for a drink, and who should come in, the girl I had seen earlier in the hotel bar, who I mentioned to Bill. I danced with her once and then returned to our table. The girl came over and sat down at our table and wouldn't leave. Finally we decided to leave and she insisted on going with us. We couldn't get a cab by ourselves because the Puerto Ricans were all in cahoots, she got in the front seat. We started to drive away and she told the driver to turn up a dark side street. Bill then told the driver to get back on the main drag, which he did and then stopped. The girl leaned over the seat and took a swipe at me with a broken mirror. I jumped out and she got out and I couldn't get away from her. I ran around the cab and Bill just leaned on the cab watching the whole thing. Finally we all got back in the cab and Bill told the driver to go down the main drag to the Navy Base. We got to the main gate and Bill told the diver to drive through the gate. There the Marine guards stopped the car and took the girl out and put her outside the gate. The last thing I heard her say was, "Don't let me catch you in San Juan again." It was a big mistake even talking to her once. We went to Bill's quarters for awhile, where we talked about what we were doing, and then I got a cab back to my hotel. I told this story when I got back to Borinquen and another guy said it sounded like the same girl who had taken swipes at him with razor blades. He had been in some kind of gambling establishment with another guy and then disappeared. His buddy found him back in their hotel room bandaging his wounds. So much for San Juan.

Last Official Flight

Miami, Florida, to

Augusta, Georgia

September 25, 1945

My last official flight was to fly with Lt. Shilling and take one surplus C-47 to Augusta, Georgia. Here it was delivered to the Reconstruction Finance Corp. in exchange for a receipt. We then dead-headed back to Miami. I retrieved the European maps which were still in the plane. These maps were used not only for navigation while we were in Europe, but were the same type of maps which adorned the War Room while at Spanhoe. I still have these maps. Lt. Shilling decided we should have a good trip to Augusta since it was our last official flight. After clearing Miami, we settled down, right over the beach or over the inland waterway, all the way up the coast of Florida. It was an extended buzz job. We passed the Banana River Naval Base, which didn't amount to much in those days. Now a days this whole area is the Cape Canaveral rocket launching area. As we neared Jacksonville, we could hear warnings on the radio about some low flying plane. So we took a wide berth around this area and cut inland over Georgia. Over Georgia we were still buzzing, this time over the thick Pine forests. We could spot an occasional house in the woods, probably belonging to some colored folk. And so we went all the way to Augusta. It was a terrific trip.

Processing to Reception Center

Camp

Blanding, Florida

September 26, 1945

After returning to Miami, I was sent to Camp Blanding, to be processed to a Reception Center near my home, namely Fort Lewis, Washington. I don't remember much about the base except that we were parceled out to various trains. The guys who had short rides to their Centers got Pullman trains. We had the longest ride and got a troop train. The cars were like boxcars with bunks, and had a small a stove at on end. I had never been on one of these before. All of the many train rides I had during training were on Pullmans. I could never figure out why we had to have the most uncomfortable and dirtiest train to go the farthest.

Worst Train Ride

Camp Blanding, Florida,

to Fort Lewis, Washington

September 27 - October 2,

1945

Needless to say, this was the worst train ride, and the longest train ride I ever had. The train was so dirty that we kept any clean cloths we had in a barracks bag and wore only dirty cloths. And then the train went through the most unscenic country I had ever seen. It went up through Georgia, Alabama, and Tennessee, and we finally got to Denver where we had a stop. Here we put on some clean cloths and went to the City. I think we may have gone to the YMCA for a swim and to freshen up. Finally we reached Portland and took a different train up to Fort Lewis. When the train went through Vancouver, it went at a slow pace. I saw Mr. Wager, one of our neighbors, standing at the Depot where he worked. I could have shouted at him but didn't. I thought he wouldn't remember me. The total trip was at least six days as I recall.

Granted 46 Days R&R

Fort Lewis, Washington,

October 2, 1945

At Fort Lewis I was granted 46 days Rest and Rehabilitation, R&R, just what I needed! I decided to go to Seattle first. I caught a Greyhound Bus and when I arrived in Seattle, my bag wasn't there. The dummies had routed my bag to Vancouver because my name and address was stenciled on the bag. So I had to wait for them to reship it back to Seattle. Then I went out to the University and looked up Dr. Moulton, the head of the Chemical Engineering Department. I was wondering whether or not to switch my major to Aeronautical Engineering or something else. He convinced me to stay with Chem.E. when I returned. After looking around Seattle and the campus, which I hadn't seen in three years, I took a bus to Vancouver.