William and Dinah Nutter's Surviving Children and their Families

William and Dinah (Ingham) Nutter had a total of fifteen children. Five of those children

(Olive, Moroni, Ingham, Lyone and Thomas) died in infancy or early childhood. Anything that is

known about their brief lives has been included in the text of the story of their parents.

The lives of the remaining ten children are going to be further detailed in the pages that follow

along with brief overviews of their spouse(s) and the families with those spouses. Among these

stories about William and Dinah's children, readers may find certain facts and stories repeated not

in an effort to fill pages, but so that each child's biographical entry can stand on its own.

At the end of each biography of William and Dinah's children are brief entries about each of

the grandchildren. These are not meant to be comprehensively biographical. However, it is hoped

these entries "place" each grandchild in time and place, record known (and hopefully, interesting)

anecdotal information plus data about the number of their descendants. While this sometimes

makes for tedious reading, it is included in an attempt to better connect the readers from these more

remote generations with the main subjects of this book.

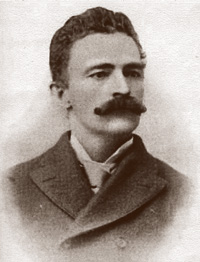

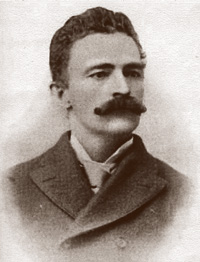

John Newton Nutter

As the eldest surviving child of his parents, John Nutter was well-positioned to remember most

of the odyssey of his parents across America, back to England and back across America.

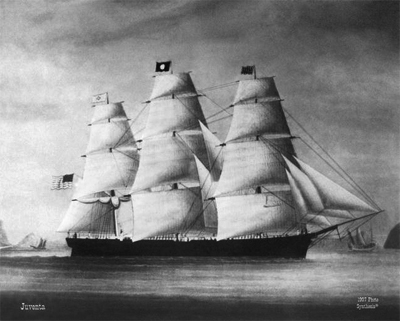

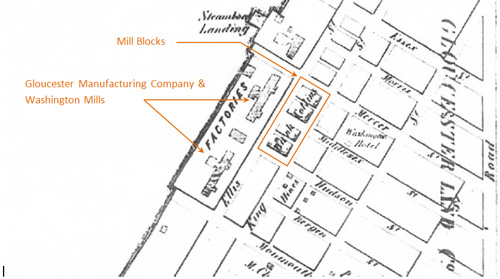

John was born 6 March, 1856, during the Nutters' brief stay in "Gloucester City" (then Union

Township) in New Jersey. The family returned to Philadelphia soon afterwards and left for Utah in

April, 1860.

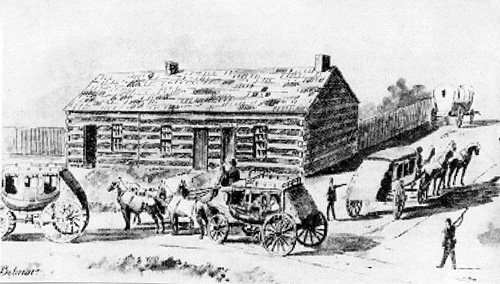

Though John had just turned four years old, certain events of the journey westward were

sharply carved into his memory; the cattle stampede that occurred on the wagon train, the morning

he was awakened to say good-bye to his little cousin who had died of whooping cough before her

burial along the trail. He recalled clearly how he was careful to be well-behaved on the journey

and how he dutifully walked westward with his family lest he suffer the fate of his little brother,

Will, who was "hog-tied" in the wagon for his own protection.

Of the time in Utah, John remembered little. It seems likely that John learned to read and write

at a Mormon school near Salt Lake City. Once the family relocated to Nebraska, he was likely

schooled at home. The events surrounding the Indian scare in late 1864, which drove the Nutters,

along with most settlers of eastern Nebraska, from their homesteads, was sharply etched into eight-

year-old John's memory. He recalled the family's time in England, meeting his grandmother and a

host of aunts, uncles and cousins for the first time. He attended at least a half term of school

there.

John grew into his early teens while the family lived in Philadelphia (1866-1869). His formal

education progressed there at the Old Bethany Presbyterian School. John assisted his mother

considerably in the daunting task of getting the six other children across the country by rail with all

of their belongings.

Once the family settled in the log cabin on the Wood River between present-day Gibbon and

Shelton, Nebraska, John sporadically attended school at the one room building that was previously

a railroad shanty throughout the early 1870s. It was sporadic not because his parents didn't value

higher education. Rather, his brawn was needed for farm work at home and he had long since

progressed well beyond the challenges offered in the one room schoolhouse situation.

As his father read voraciously, he followed a path directly behind his father often through the

same books. On those occasions when they worked together, John and his father enjoyed deeply

intellectual discussions. Not surprisingly, John's life philosophy very much mirrored his father's.

He developed as an atheist and was very interested in all of the natural sciences. Unlike his father,

he carefully tracked current events and politics for his entire life, assessing them from a liberal

Democratic point of view.

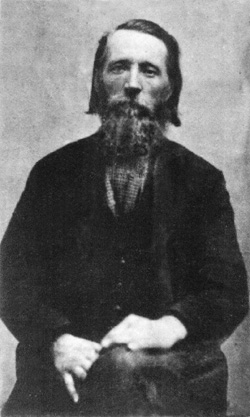

John grew into a very handsome young man sporting a full head of black, curly hair. He grew

a moustache which had a decidedly reddish tinge to it. He was average-to-tall in height and was

built like one would expect any young man to be built who had worked hard on a farm.

John leased a tract of school land in 1878 totaling 164 acres and began farming it in his own

right. Soon after, he bought the acreage and bought and swapped some additional land. The

eventual total of his land holdings came to nearly 600 acres.

In 1880, John met Anna Carlson, while serving as a deputy for Buffalo County Sheriff Simon

Seeley. Anna had been born 5 August, 1862 in Oskarshamn on Sweden's southeastern-most coast

to Carl and Marta Catherina

(Nilsdotter) Carlson. Her parents had come to Varna, Illinois with the

family in 1870 and then to Phelps County, Nebraska in 1879. Because she had begun her

education in Sweden and finished in Illinois, Anna was as comfortable with the Swedish language

as she was with English. Some of her correspondence with "My Own Darling John" Nutter still

survives. In it, she articulates her affection very well and reveals some profound, typically

Scandinavian, melancholy over her father's dislike for the "godless" John Nutter.

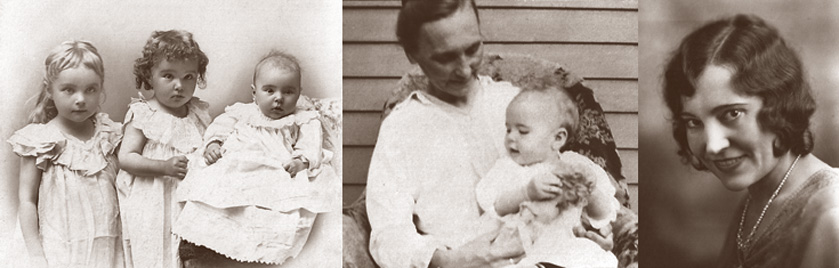

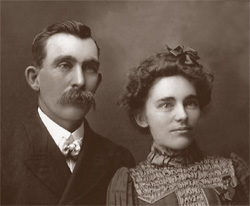

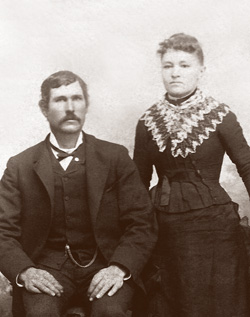

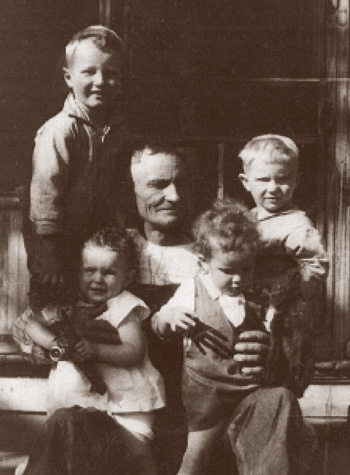

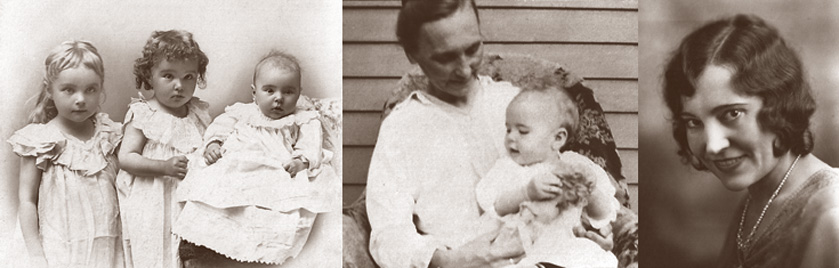

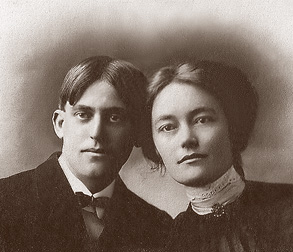

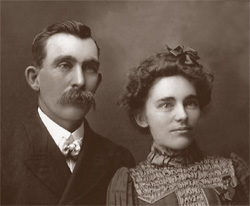

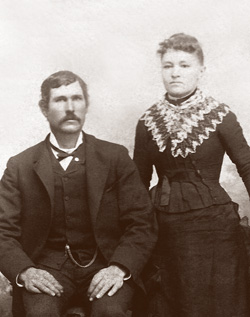

John and Anna Nutter

Children of John and Anna Nutter. From the left: Elsa, Effie, Olive, Herbert, with Beatrice in the chair.

Nevertheless, John and Anna were married on 2 May 1881 while John was serving as a deputy under Buffalo

County Sheriff Simon Seeley. Their wedding occurred in Kearney at the home of Sheriff Seeley

and his wife Ida who was Anna's sister and likely the person who introduced John to Anna. She and

John settled on his homestead in Platte Township, away from the "Fort Farm Island" holding for the first two years. John then

moved into a small farmhouse on the Fort Farm Island farm and set up his wife and growing family

in a larger home on a farm between Shelton and Gibbon; the "home" farm. This arrangement

appears to have given Anna some pause about the likely long term success of their marriage.

However, in the first six years of their marriage, John and Anna became the parents of four

children. After the birth of the fourth child, Anna was unsuccessful in carrying some number of

pregnancies to full term. A fifth child was born in 1891.

As might be expected, John's living arrangement (separate from his wife and family), Anna's

frequent pregnancies, John's growing enjoyment of alcohol and, at the very least, the rumors of his

infidelity took its toll on the young marriage. Her daughters would later say that, had Anna lived,

she would have likely divorced John. However, that was not to be.

John Nutter was elected Buffalo County Sheriff in 1892. He, Anna and the children moved into the

home in Kearney previously occupied by Anna's sister Ida and her husband, Simon Seeley, (the outgoing

sheriff). Anna then discovered she was pregnant once more. Some have said she attempted to

terminate the pregnancy; others claim she simply miscarried. Whatever the case, she developed

blood poisoning and died suddenly 23 March, 1893.

John Nutter was devastated. Despite his inclination to live life on his own terms, Anna was, no

doubt, the love of his life. His mother, Dinah, and his newly-wed sister, Jennie Nutter Hogg,

stepped into the breach and assumed the care of the five young children.

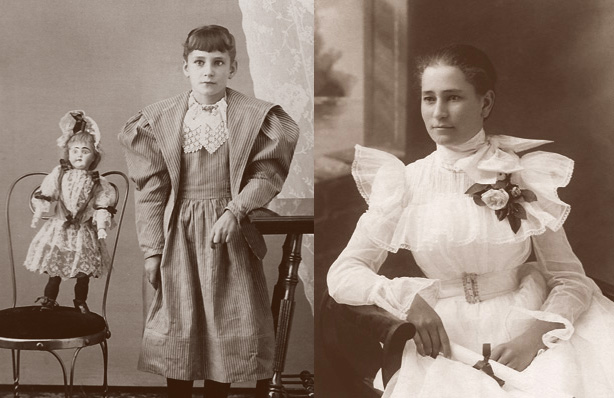

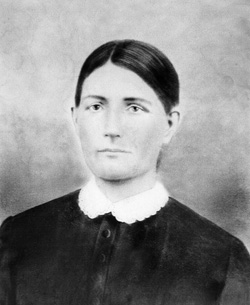

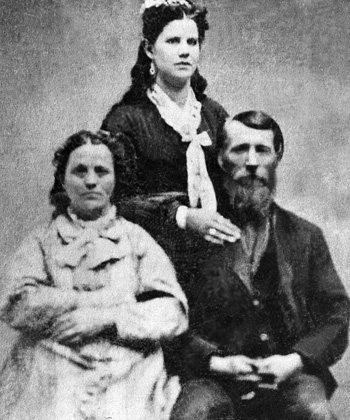

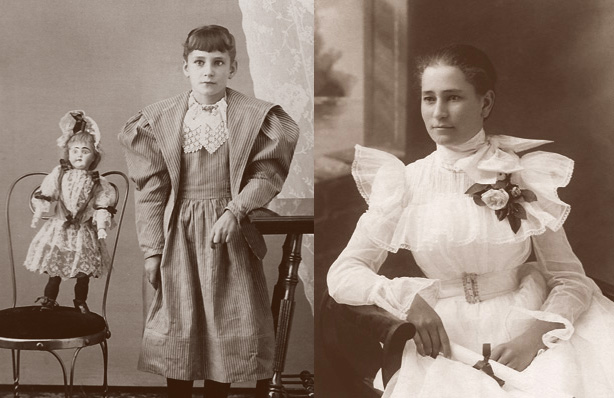

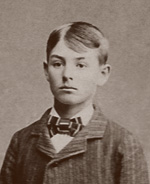

Jennie Reinholdson Nutter as a young girl in Sweden

In the Summer of 1893, John met Jennie Reinholdson, a 22-year-old visitor from Sweden.

Jennie had been born 27 March, 1871 in Ost Furtan, Brunskog, Varmland, Sweden to Britta

Jansson, a teacher in the village who died a few days after Jennie's birth. Jennie's father, Olaf

Reinholdson, allowed Britta's mother to assimilate Jennie into her own family and Jennie was raised

with an uncle who was close to her own age. Jennie had come to Nebraska to visit that uncle where

she met John Nutter. After John proposed marriage, Jennie abandoned her plans to return to her

native country.

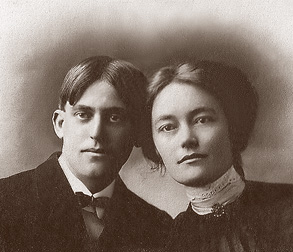

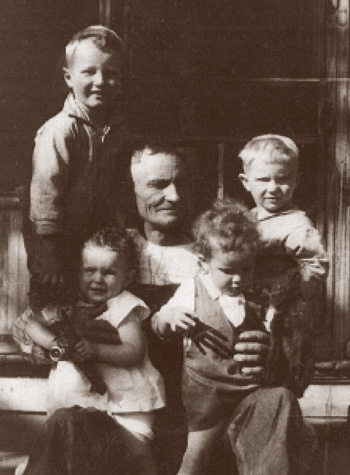

John and Jenny Nutter

On Christmas Day, 1893, John Nutter and Jennie Reinholdson were married. Considering

Jennie had nothing but a rudimentary understanding of the English language at that point, it is hard

to know for sure if she realized the enormity of the task she faced. Marriage to John Nutter under

the best of circumstances was bound to be hard work. He continued to insist on separate

residences. However, there were his five children with Anna to raise. Plus, they would have

children of their own as well; three girls in the first five years, a son five years later, another son

nine years later, then a daughter three years later as Jennie neared her forty-fourth birthday.

John Nutter served a second term as Buffalo County Sheriff and then returned to Fort Farm

Island in 1896. Jennie moved into the other farm east of Gibbon with the children. There, she

"executed her task" with such grace, strength and stoicism that she earned the enduring love and

respect of all who knew her, particularly her stepchildren.

Jennie's mettle was sorely tested at the end of 1903 when she gave birth to her first son, Harold.

Already at home were three daughters under ten, two teenaged step-daughters and a teenaged step-

son, plus another step-daughter in her early twenties. Someone suggested that if the step-son,

Herbert, were to move westward with his Aunt Jennie Nutter Hogg, her husband Will and their two

sons, it would ease the growing chaos at home, free up a bedroom, and perhaps, offer Herbert a

unique opportunity to prosper. All of the concerned parties agreed and Herb went to Oregon.

A few years later, in 1906, John’s mother Dinah was widowed. She was intent, after years of

being unable to travel because of her husband's illness, to go to the northwest and visit her three

daughters and numerous grandchildren who lived there. Fully aware that John’s wife Jennie was

still very overburdened by her family responsibilities and that John was of no significant help, she

proposed that the remaining daughters of John's "first family" still at home, Olive, Elsa and

Beatrice, accompany her on the trip west. And so they did.

John Nutter continued to live separately from his wife and family. His drinking continued and,

it is believed he fathered at least one other daughter with a local woman during this period. Still, he

built up substantial wealth over the next decade through hard work and his sharp business acumen.

His lifelong thirst for knowledge was seemingly never quenched. He was well-respected in the

community as an extraordinarily ethical businessman.

As a boy, John's chores included procurement of wood for fuel. He was therefore acutely

aware that the Wood River Valley area lacked mature trees. As a result, he made it a life-long

priority to plant literally hundreds of trees, perhaps thousands, on his properties. John was also a

great story-teller, always at the ready to tell tales to anyone who would listen of his family's early

adventures during his formative years.

John and Jennie had another son, Donald, in 1912, then their last child, a daughter, Jean, three

years later when he was nearly 59, she nearly 44. In that same year, 1915, John retired from active

farming allowing tenants to farm the Fort Island acreage.

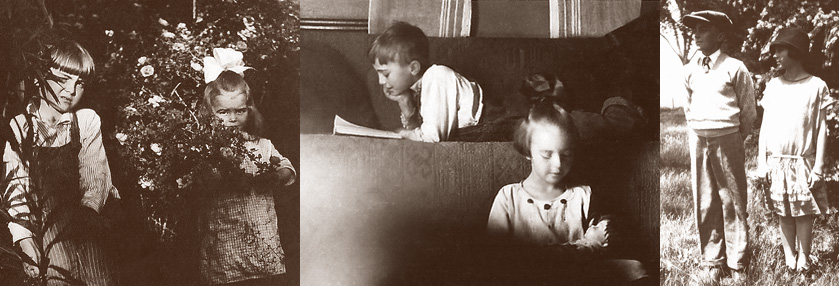

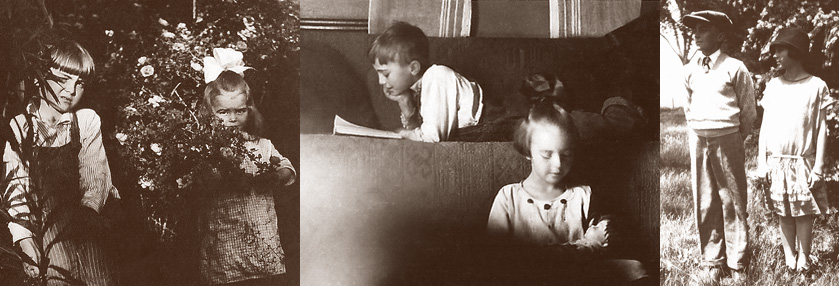

Don and Jean Nutter - Youngest children of John and Jenny Nutter

Left

Left: Inez, Hilda "Stub", and Marge Nutter;

Center: Jenny and Jean;

Right:

Olive Nutter and her half-brother Don (Don stayed with Olive and Charlie for several months)

Jean, Don, Harold, Marge, Hilda, and Inez Nutter

In 1920, John asked his son Herbert to return from Oregon and farm the Fort Farm Island

acreage. It seems he then moved into the house at the home farm where his wife and children

lived. None of this went well. Herbert soon returned to Oregon with his wife and daughter. John

returned to his solitary existence in the house at Fort Farm Island. In an odd example of John's

code of ethics, John quit drinking alcohol that same year as the eighteenth amendment and the

recently-passed Volstead Act would have made him an outlaw had he continued to imbibe.

As the years passed, most of John and Jennie's family married and/or moved away until just the

youngest two, Donald and Jean were at home with Jennie. Son Herbert passed away in 1931 in

Oregon. Donald gradually began taking over the farm on which John lived. John's health began to

fail in the 1930s as he suffered a series of strokes. One morning late in the Fall of 1935, Donald

discovered John in his chair, paralyzed by yet another stroke. He took him back to the "home farm"

where he died a few weeks later on 10 December.

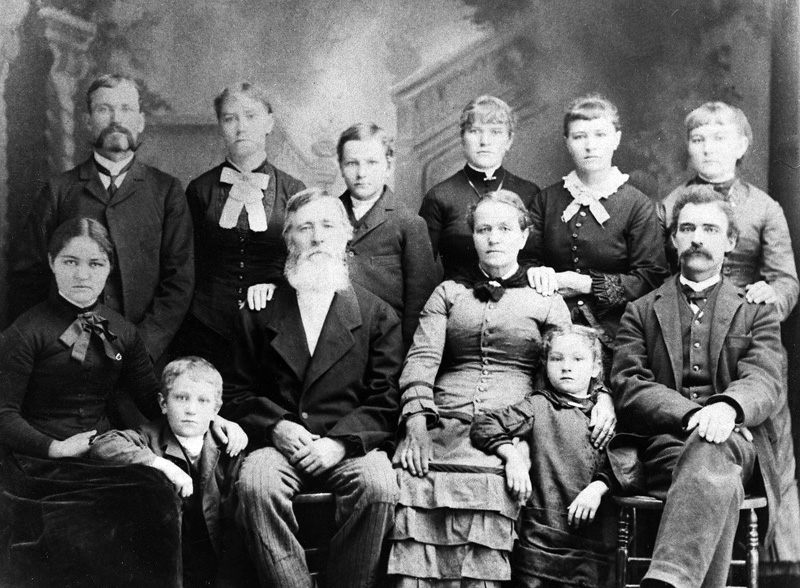

John Nutter's widow (Jennie) and his ten living children, in ascending age, together for the

first time on the occasion of John Nutter's funeral in December, 1935. Left to right; John's

widow, Jennie; Jean Nutter, Don Nutter, Harold Nutter, Marjorie Nutter, Hilda Layman, Inez

Reynolds, Beatrice Hogg, Elsa Evans, Effie Graham and Olive Holmes.

A week later, all ten of John Nutter's living children attended his funeral. Five of his "out-of-

state" daughters came to Nebraska and some actually met a few of their siblings for the first time

ever. Despite the miles that would remain between them, each made an effort to maintain contact

with and visit the others for the rest of their lives.

Of course, all this delighted Jennie. She maintained a cordial and loving relationship with her

children and step-children, and reveled in the grandchildren and great-grandchildren that came

along. After John's death, Jennie’s youngest children, Donald and Jean, spent the horrendously hot

summer of 1936 refurbishing the home on Fort Farm Island and moved Jennie into the house

where her husband had spent so many solitary years. Donald and his mother lived there for

another 35 years.

Though Jennie had lost contact with her family in Sweden many years before, her daughter

Jean re-established contact in 1965 through her genealogical research efforts. Jennie's father, who

had stepped out of her life just days after she was born, was found to have married and raised a

family in northern Sweden. In 1969, when Jennie was ninety-eight, she finally met her sixty-four

year old "kid brother", Thorvald Reinholdson, who traveled from Sweden to meet her and her

family.

Jennie died in November, 1970, five months short of her one hundredth birthday.

Reunion of west coast children of John Nutter and their families

Reunion of west coast children of John Nutter and their families

Standing: John Hogg and his wife Beatrice (Nutter) Hogg are

2nd and 5th from the left. Their daughter Betty (Hogg) Nims is 7th from the left. Beatrice is

holding her first grandchild, Betty's daughter Linda. Standing at the left is R.W. "Will" Hogg, older

brother of John Hogg. 8th from the left is his daughter Margaret. 3rd and 6th from the left are

Johnny Evans and his wife Elsa (Nutter) Evans, Beatrice's older sister. 4th from the left is Inez (Nutter)

Reynolds, also a sister of Beatrice. Inez's son Bob Reynolds is 6th from the right. 5th from the

right is Beatrice's Aunt Jennie (Nutter) Hogg, wife of Will Hogg. 3rd and 4th from the right

are Olive (daughter of Johnny and Elsa Evans) and her husband Thorvald Jorgenson, followed

by Evelyn and John Evans, Jr. (far right) with their son Richard down in front of them.

Seated in front: From the left, Spence (1st), Ladd (2nd), Nancy (3rd), Billie (7th),

and Jean (last on the right) are the children of John and Beatrice Hogg. Only their son Dick is

missing. 6th from the left is Inez's youngest son, Dick. Seated to the left of Jean in the

picture is Edna Elizabeth (Nutter) Pearson, sometimes referred to as Betty, and sometimes

as Steve (reason unknown). The other woman seated in front of Betty Nims is Ramona "Mona"

Evans, youngest daughter of John and Elsa Evans. The young boy seated in front of her is John Evans

(son of the aforementioned John and Evelyn Evans). To the right of Mona is Dick Reynolds, son of Inez.

The Children of John Nutter and Anna Carlson

Olive Nutter

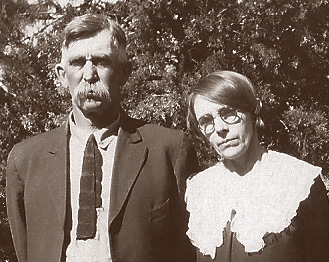

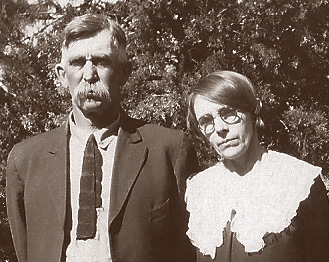

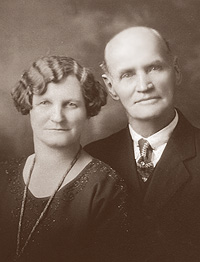

Charles and Olive (Nutter) Holmes

Olive Kathryn Nutter (1882-1955) - taught school for a few years in Buffalo County

and was boarding with her aunt, Louise Nutter Miller at Ravenna in 1900. In 1906, she went west

with her sisters and their grandmother. Olive, however, went no further than Denver, Colorado, as

a romance had bloomed for her as she passed through that area. She married Charles Holmes

(1878-1949) early in 1907 and the marriage, in the long run, was less-than-happy and childless.

"Ollie" and Charles made their home in Englewood, Colorado where they lived quite separate lives.

Charles spent the entire marriage socializing with a rather unsavory crowd. Olive joined social

clubs and earned the love and respect of many in her community. She died of a heart attack in

1955.

Taken in Denver, Colorado, likely in February, 1907, around the time of Olive Nutter's marriage

to Charles Holmes. Reuben Miller and Louise (Nutter) Miller flank the "passengers" in the car.

Their children, Gerald and Ruby are at the front. Olive (Nutter) Holmes is in the next row with

her grandmother, Dinah (Ingham) Nutter. Charles Holmes is at the back-center.

Charles and Olive (Nutter) Holmes in their backyard.

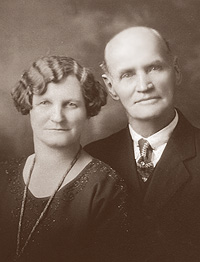

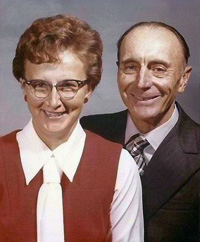

John and Effie (Nutter) Graham

John and Effie (Nutter) Graham

Effie Diana Nutter (1883-1978) - was named "Euseffa Irvine" at birth, but her name

was changed very early on in her life. In 1903, she married John Edward Graham (1871-1966), a

local farmer, with whom she had two daughters. When the younger daughter, Georgia Beatrice

(1908-1925), died suddenly of a throat infection during her senior year in high school, Effie was

plunged into mourning and a profound depression which lasted for years. John retired from

farming in 1929 and moved with Effie and their surviving daughter, Amy, to a small home in

Gibbon where John died after being retired for thirty-seven years at the age of 95. Effie died

thirteen years later, also at the age of 95. Daughter Amy Renetta (1903-1999) moved to Denver,

Colorado and had wed Max Lowdermilk (1910-1966) in 1935 who built a large retail bakery chain

and, unfortunately, lost the same. She and Max had no children. Amy and her mother were both

widowed within a few months of each other in 1966. Coincidentally, like each of her parents,

Amy died at the age of 95.

(from left) Amy & Georgia Graham; Georgia & Amy Graham (1908); Amy Graham (1927); Georgia Graham

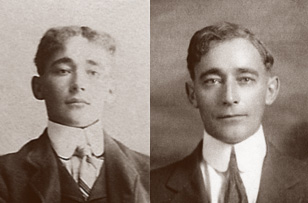

Herbert Nutter

Herbert Spencer Nutter (1885-1931) - was named for a great nineteenth century

English philosopher whom his father admired. He moved to Oregon with his aunt, uncle and

cousins in 1904 and worked his way up in the Wells Fargo Company in Portland. In 1911, he

married in Salem to Edna Eugena Bacon (1890-1969), a native Oregonian, with whom he had a

daughter. The marriage supposedly suffered, in part, because of Herb's avocation as a musician.

An accomplished clarinetist, he socialized with other musicians and was subject to the temptations

of the "underground culture" associated with musicians in that era. In a venture bound for failure,

Herb returned to the simple life of a Nebraska farm with his wife and daughter in 1920. In 1921,

he returned to Portland, Oregon and the employ of the Northern Pacific Railway Company where

he worked until his death in 1931 from Bright's Disease. He and Edna had divorced three years

earlier after which she married two more times. Herb's only daughter, Edna Elizabeth “Betty"

(1912-1973), married Walter Malvern Pearson and had an only son, Terry Spencer Pearson (born

1945). He has six children and at least five grandchildren.

John and Elsa (Nutter) Evans family: Olive (top left), John Jr. (top center), Howard (bottom

right) and Rosalie (seated on her mothers lap)

Elsa Theodora Nutter (1887-1990) - moved to Salem, Oregon, when she was 19

years old. She began working in a prune packing plant where she met John William Evans (1878-

1961) whom she married shortly afterwards in 1907. The couple moved south to Coos County for

six years where they had a dairy farm and where their first three children were born. They returned

to farm near Salem where their last two children were born. After her husband died, Elsa continued

to live on her own during her eighties (during which time she laughingly referred to herself as an

"octa-geranium") and well through her nineties. Sadly, she survived all five of her children and

three of their spouses. Additionally, macular degeneration robbed her of most of her eyesight. She

died in a nursing home, still spry and alert, just 5 days short of her 103rd birthday, survived by 10

grandchildren, 17 great-grandchildren and several great-great grandchildren.

Three youngest children of John and Elsa (Nutter) Evans: John Jr. (left), Rosalie (center),

Ramona (right)

John and Beatrice Hogg and their three eldest children: From left, John "Lad", Jean, and Richard "Dick".

John and Beatrice Hogg

Frances Beatrice Nutter (1891-1984)

- was always known as “Bea" or "bea-AT-ris".

She moved to Salem with her sister Elsa and graduated from high school there. After teaching

school for two years, she married in 1912 to John Alexander Hogg (1882-1964), a fellow

Nebraskan, who was a younger brother of her uncle (by marriage) Will Hogg and aunt (by

marriage) Lizzie Hogg Nutter. They had 3 sons and 4 daughters, all born in Vancouver,

Washington, where John was the proprietor of a book and stationery store. The family did very

well and John entered into local politics serving as city treasurer and mayor. In the 1940s, he made

an unsuccessful run for the U.S. Senate. However, John and Beatrice drifted apart late in life

and John moved into a room in the basement of their Vancouver house on Franklin Street. The bookshelves

lining nearly every wall spoke to John's continued passion for reading and self-learning. He died

peacefully in 1963 at age 81. Beatrice returned to school after World War II and became a licensed

practical nurse. She worked at Vancouver Memorial Hospital in that capacity for 13 years, finally

retiring at age 73. Beatrice remained active and very healthy as she passed her ninety-third birthday

in November, 1984 but died on the following Christmas Eve as a result of injuries suffered in an

auto accident. Her seven children were all college educated, employed variously in teaching, engineering

(chemical and electrical), pharmacology, etc. Most of the 24 grandchildren are similarly well-educated.

Nearly all live in the west and southwest.

Beatrice Hogg and children (photo taken in 1963 at the time of John Hogg's funeral): (from left) Lad,

Jean, Beatrice, Betty, Billie, Nancy, Dick, Spence

Bill Jansen |

Jean (Hogg) Jansen |

Nancy Ann Jansen |

Diana Jansen |

Richard "Dick" Hogg |

Bettye "Self" Hogg |

Maureen Hogg |

Joanne Hogg |

John E. "Lad" Hogg |

Pauline "Pollee" (Sandel) Hogg |

Patsy Hogg |

Jeffrey P. "Jeff" Hogg |

Frank Leslie Nims |

Betty Miles (Hogg) Nims |

Linda Jean Nims |

David John "Dave" Nims |

Nancy (Hogg) Perry |

| |

Daniel Fred "Danny" Nims |

Robert Spencer "Spence" Hogg |

Margaret (Aja) Hogg |

Frederick L. "Freddie" Meissner |

Marilyn Frances "Billie" (Hogg) Meissner |

Pictures of the John A. & Beatrice (Nutter) Hogg children and grandchildren taken by Freddie

Meissner, who was a photographer by trade. (circa 1954 - before Nancy was married to Thorton

Perry, and before the youngest grandchildren were born.)

The Children of John Nutter and Jennie Reinholdson

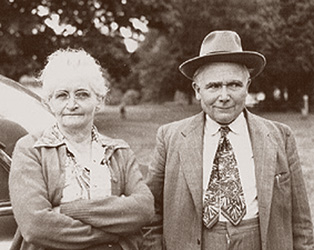

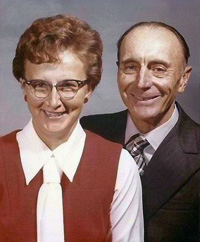

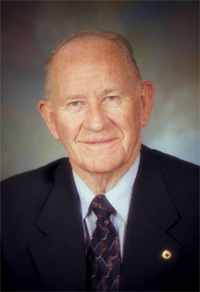

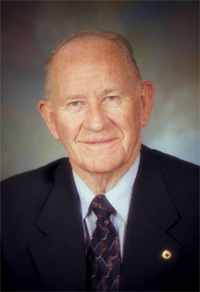

Maynard Everette Reynolds, called "M.E.", shown at his home in Corvallis, with his high

school sweetheart and life-long wife, Inez

Graduation photo of Inez Virginia Nutter

Inez Virginia Nutter (1894-1968) -

was, at first, given the Swedish name Ina Signe

by her Swedish mother. After graduation from high school, she married Maynard Everette "Everette"

Reynolds (1895-1994) and moved to Red Elm and then, Dupree, both in South Dakota. During

most of their thirty years there, they farmed and Inez taught school. However, at various times,

Everette also sold real estate, published a newspaper, ran a restaurant and a grocery outlet, worked

as a milkman and served as the County Register of Deeds and auditor. In June, 1942, the couple

moved to Corvallis, Oregon where they lived the rest of their lives. In retirement, they travelled

often to visit family. A car accident on one of these visits precipitated Inez' death from an

embolism while in a Decatur, Illinois hospital. Everette survived her by nearly a quarter century,

dying two months after his ninety-ninth birthday. Their eldest son, Robert (1915-2006) moved to

Portland, Oregon in 1936. He learned carpentry then in Corvallis, Oregon and eventually became a

contractor. His parents joined him there with his younger brother in 1942. Except for a stint in the

Sea-Bees during World War II and a year in Alaska, he lived in Oregon until 1952 when he moved

to Yerington, Nevada. He had two children and 3 grandchildren. Everette and Inez' only daughter,

Janice (1918-1966) married in 1938 to Clyde Baker (1912-1985) who was pursuing a career in the

military. The couple was stationed in Alaska for many years and their two daughters plus one of

their two sons were born there. They were also stationed in Ankara, Turkey for a while. After the

family moved to El Paso, Texas, Janice was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis. Her health

deteriorated and her marriage and family life were very strained by her decline. Janice died in

1966. Some of her descendants now live in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, and a few live in Texas,

Arizona and California. Everette and Inez' younger son, Richard Everette Reynolds (1930- ) had

three sons with his first wife and a daughter with his second wife. He continues to live in Corvallis,

Oregon with his third wife.

Everette Reynolds

Everette and Inez Reynolds family. From the left, Inez holding her youngest child, son Dick Reynolds;

son Bob Reynolds; Everette Reynolds, holding onto his granddaughter Patricia Anita Baker; daughter Janice

(Reynolds) Baker, wife of Clyde Baker and mother of Patricia.

Nancy Sue Polan

(Carolyn Anne Layman)

Hilda Marguerite Nutter (1896-1985) - used the name Margaret legally throughout

her whole adult life, but her family always simply called her "Stub" - a nickname surrounded by

much folklore as to its origins. The favorite explanation seems to be that it referred to her well-

known stubbornness. After teaching school in Shelton for a few years, she married in 1920 to

Charles Hooker Layman (1894-1942), a veteran of World War I and a Seventh Day Adventist.

Charles worked in the building trades for years in the area of their home at Grand Island, Nebraska

and died after a fall from scaffolding at work. Stub lived a meager existence for the balance of her

life in Grand Island. Elder son Charles (1921-2006) lived near Washington, DC and had three

children from two marriages. The younger Layman children were twins born in 1925; Keith was in

the navy during World War II and moved first to Pendleton, Oregon, then to Southern California

where he died in 1983. He had one son from his first marriage, three children from his third

marriage. His twin sister Carolyn, had two daughters, Carolyn Anne and Anita Sue. Though they

never married, Carolyn's father was George Julius Morgan. Anita's father's last name may have been

'Heller' or 'Keller'. Carolyn Ann was given up for adoption, and her adopted name is Nancy Sue Illsley.

She married Darrell Polan, Sr. She now lives in in Omaha Nebraska.

[Thanks to Zachary Christensen, loving grandson of Nancy Sue (Layman) Polan, for the updated information and the picture.]

Marjorie Nutter

Marjorie Isabel Nutter (1898-1990) -

taught school after graduation and then, in

1921, began working for Northwestern Bell Telephone Company in Omaha, Nebraska and

completed her studies at a business college there. During the 1920s, she met a wayward Danish

Count with whom she fell in love. However, the Count mysteriously disappeared while on a

motorcycle tour of the west coast. It seems likely he perished in an accident along one of the

coastal roads. Some family members believe that this tragedy had much to do with the fact that

Marjorie remained unmarried for the rest of her life. In 1928, she moved to Minneapolis,

Minnesota, where her employer's headquarters was located. She retired in 1963 from the telephone

company and began work for the Minnesota Institute of Arts. Even after a second retirement, she

served as a volunteer for the Institute and for the Minnesota Symphony Orchestra. She also did

volunteer work for 35 years at the local Methodist hospital and she had served during World War II

as a Red Cross nurse. After suffering a stroke in 1984, she moved to a nursing care facility in

Boulder, Colorado to be near family. She died six years later.

Harold Nutter

Harold Nutter on the sax

Harold enjoyed gardening

Harold Kenneth Nutter (1903-1999) - who was originally named Harold Sydney

Nutter, occupied a unique, almost solitary position amidst his many siblings and half siblings. By

the time he was three, his five elder half-siblings had either married and/or moved away. His next

sibling wasn't born until almost nine years later, affording him an "only child" status for some time.

He became an accomplished musician, adept with the saxophone, clarinet and violin. After

graduation from Gibbon High School, he married Josephine Scott (1906-1972) in 1923 and soon

thereafter, like his father, decided to buy his own acreage to farm in his own right. He farmed the

land northeast of Gibbon until his retirement in 1970 and also worked as a regular and substitute

mail carrier in the area from 1950 to 1972. Harold enjoyed nearly 30 years of retirement and lived

on his own amidst his family near Gibbon until shortly before his death in 1999 at the age of 95.

Harold and Josephine had a daughter, Genevieve (born 1925) who trained as a nurse in Lincoln,

Nebraska after marrying Gordon Robb. She has three daughters and four grandchildren. Harold

and Josephine also had two sons. Richard Harold Nutter (1929-1996) had three daughters with his

wife, Grace Osler, from whom they had their five grandchildren. He farmed and, like his father,

served as a substitute mail carrier until taking the job full-time. John Ronald Nutter (born 1933)

married in 1951 to Ruby Loewenstein and had 2 sons born during the time they lived in Kansas.

They eventually returned to the area near Gibbon, Nebraska and have 5 grandchildren and several

great-grandchildren in the area.

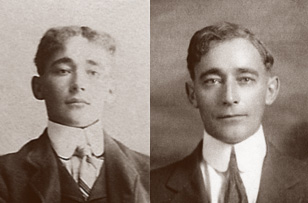

Don Nutter - High school graduation

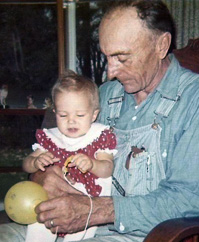

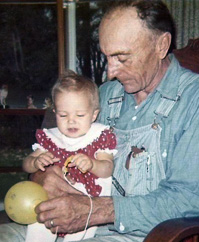

Don Nutter and daughter Lori

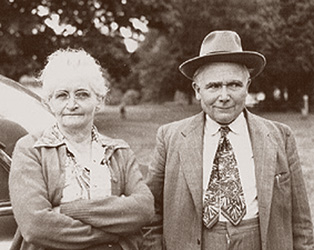

Don and Margaret Nutter

Donald Oakley Nutter (1912-1980) - was given his unique middle name for no other

reason than it facilitated his initials spelling his nickname. He graduated from Gibbon High School

like his siblings and began working his father's Fort Farm Island land while in his teens. As his

older half-brother (Herbert) had opted out of farm work and returned to Oregon and because his

full brother Harold had purchased his own land, Don's father eventually turned over all of his

acreage to Don. There was also an understanding that Don would take care of his mother for the

rest of his life - a duty Don gladly and lovingly undertook. Two months after his mother's death, as

he approached his fifty-ninth birthday, he married Margaret Estella Mohn Bennett (born 1933) who

had recently come out of a failed marriage. With Margaret came a ready-made family of four sons.

Also, Don and Margaret had a child together in 1972 as he approached his sixty-first birthday. Lori

Lynn Nutter would know her father just a short time though as Don died of an apparent heart attack

eight years later. Lori married in 1991 to Heath Gregor.

Family of Yale and Jean Nelson (center). Clockwise around Jean are her husband, Yale Nelson;

daughter Marilyn "Lyn" Nelson, Robert Nelson, Steven Nelson and Thomas Nelson.

Jean Nutter - Hastings College (1935)

Jean Helen Nutter (1915-2003) -

was the last child of her parents, born when her

father was fifty-nine and her mother was forty-four. She graduated from Gibbon High School and

attended Hastings College in Hastings, Nebraska. After graduation in 1939, she was a social worker

in Hastings but eventually moved to Denver, Colorado. There she was married fellow Nebraskan

Yale Roy Nelson (born 1918) in 1942. The two had met while at college in Hastings. Jean and

Yale moved several times in their marriage as Yale worked as a pilot for United Airlines (three of

their children were born during two different tenures in Chicago, Illinois - the other child was born

during their time in Seattle, Washington). Eventually, they returned to the Denver area where Yale

spent the latter part of his career at the United Airlines Training Center as an instructor. As she

raised her family, Jean pursued the rather daunting task of maintaining regular, loving contact with

her "immediate" family along the west coast and in Colorado and Nebraska, some of which was

facilitated by her access to United Airline passes. As her interest in family history burgeoned in the

1960s, she expanded this interest in family to Sweden, England, and to more of the USA. She was

an avid and tireless researcher and is responsible for collecting the major portion of the information

found in this book. All of Jean and Yale Nelsons' children live in the greater Denver area. Son

Robert Yale Nelson (born 1945) is retired from the telecommunications industry as is his wife. He

has a son and daughter by two previous marriages. Son Steven Arthur Nelson (born 1947) is self-

employed and is married, has a step-daughter and grandchildren. Son Thomas Cavett Nelson (born

1952) is married, has a son and daughter and is a successful businessman in the field of medical

care. Only daughter Marilyn Jean Nelson (born 1955) is married and has a daughter. Both she and

her husband John Heins perform, compose and teach music.

William Hingham Nutter

William and Laura Nutter

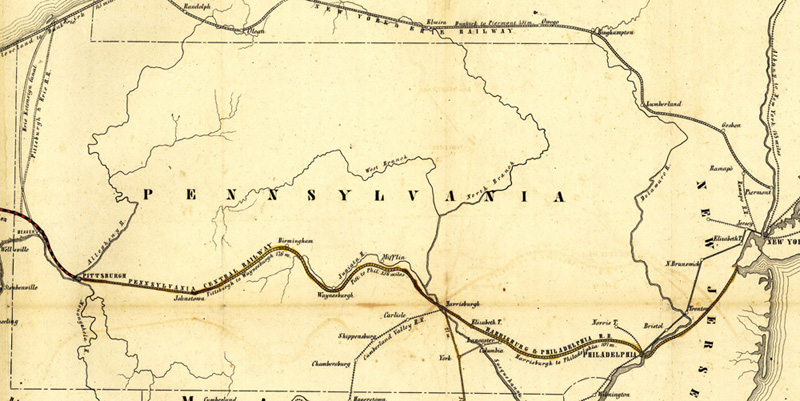

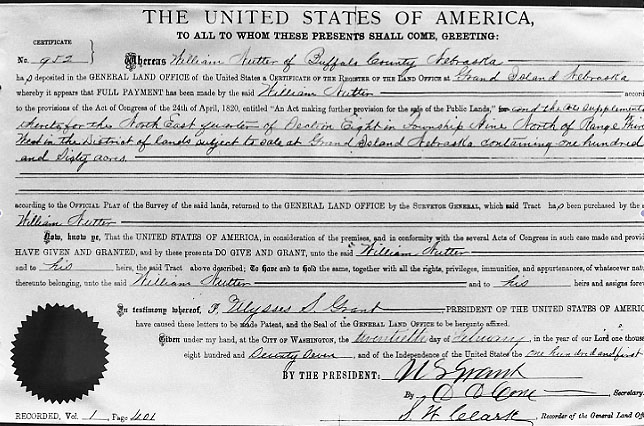

William and Dinah (Ingham) Nutter's second surviving son was born on 9 June, 1859 in

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His identical twin, Hingham William Nutter died soon after birth.

Throughout his life, he always used the name William H. Nutter. However, the initial "H" was

derived from an incorrect rendering of his mother's family name of Ingham. (Speakers of the

Lancashire dialect in Northern England drop the initial "H" in most words and often insert an "H”

when a word begins with a vowel).

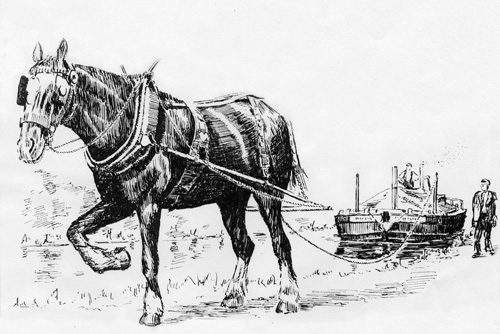

"Will", as his family called him, was a few days short of his first birthday when his parents --

after traveling by rail and water from Philadelphia to Florence, Nebraska --began the journey by

wagon train to Salt Lake City, Utah. In later years, Will would relate that he was "hog-tied" into the

wagon by his parents who feared he could fall out undetected. Will contracted whooping cough like

so many other children on the way. Fortunately, he survived, unlike so many others.

Naturally, Will had no recollection of his family's time in Utah (1860-1862). He had no

substantial memories of their retreat to, and their first time living in, Nebraska. His memories

became somewhat clearer of his family's return to England in 1865 when he was six years old. He

remembered some of his many cousins near to his age. He clearly recalled the time in Philadelphia

after his parents returned to the USA. He began attending Old Bethany Presbyterian School there

and was edified by the responsibility he shared with his elder brother, John, as they watched over

their younger sisters on the long journey by train back to Nebraska in the summer of 1869.

Will began attending school in an abandoned railroad workers' shack near Wood River Junction

(now Shelton), Nebraska. He had easily mastered reading and printing early on, but curiously, he

was a teenager before he became proficient in cursive writing. Like his father and his elder brother

John, he was a voracious reader and a life-long atheist with a strict moral code. It was not unusual

for the three of them to be engaged in long theoretical, philosophical and scientific discourse at

home or while at work on the farm.

Unlike his brother John, Will had no particular affection for alcohol and was the "dutiful" son -

- his father's faithful right-hand man on the farm with seemingly no particular interest in striking out

on his own. He honed his carpentry skills during the building of his family's octagonal house,

presumably guided by the anonymous finish carpenter who lived with the family in 1887 while the

house was being built. Once the carpenter moved on, Will had his own bedroom. That one room

he had to himself was comparable in size to the entire log cabin in which all of his family had lived

in for the previous twenty years. A few years later, in the spring of 1890, thirty-one-year-old Will

Nutter met a beautiful and petite sixteen-year-old girl, Laura Myrtle Comstock, at a dance in

Gibbon.

Laura Myrtle Comstock had been born in Lisbon, Illinois on 22 February, 1874, the second

child and eldest daughter of (George) Elmer Comstock and his wife, Evalina Rosaltha (Eastman)

Comstock. The parents and nine children moved to Sturgeon Bay, Wisconsin in 1888 where

Laura’s mother and little sister, Cora, died. The remaining family then moved to Gibbon, Nebraska

in March, 1890. Originally, Elmer Comstock (1843-1915) was from Clinton, New York. His

grandfather had come to that area of New York from Rhode Island where his ancestors had lived

for two centuries since coming from England. His marriage to Evalina Rosaltha Eastman (1846-

1889) was not particularly well-received because Evalina’s father, Peter Eastman had married

Abigail Smith, a "Negro woman" who became mother of his children. Laura Comstock was well

aware of her mixed heritage and cherished it because it came to her through her much-beloved

mother. However, she was also discreet about it when she felt she needed to be.

Will Nutter and Laura Comstock were married at her father's home in Gibbon on Thanksgiving

Day, 1891 (November 26). Fifteen months later, she gave birth to their first child. Over the next

twenty years, a dozen more children came along.

Family picture of William and Laura Nutter. (Left to right) Perry Nutter; his father, William Nutter;

Pearl Nutter; Orville Nutter; their mother, Laura Nutter; Wellington Nutter

Family picture of William and Laura Nutter about 1902. (Left to right) Wellington Nutter;

William Nutter (the father), Perry Nutter; Pearl Nutter; Banks Nutter; Laura Nutter (the mother)

and Orville Nutter

Will bought his own farm adjacent to his parents. It seems likely that his parents contributed

significantly to the purchase in recognition of his long service on the family farm. Will paid the

mortgage off very soon after 1900. A few years later, Will became relatively well-off financially

and began to speculate in land and oil fields near Edinburg in southern Texas. Unfortunately, he

parted with a great deal of money and bought property sight unseen.

In 1909, Will and Laura left their five youngest children in the care of their oldest daughter,

Pearl, then age 14, and headed to Texas with their four older boys. These older boys fondly

remembered their time in Texas, riding motor bikes and horses. For Will and Laura, it was a sad

time as they realized they had bought land that was virtually worthless. The land was dry and

infertile and drilling for oil would have required further capital investment. They sold the land at

an enormous loss.

The Nutters rebounded financially rather quickly even under the strain of a large and rapidly

growing family. Will's farm was a lucrative endeavor though he always seemed to be looking

elsewhere for alternative or additional ways of making a living or, at least, additional income.

During these years, Will seriously entertained thoughts of emigration to Australia or New Zealand

but set his sights on more conservative alternatives after he passed his fiftieth birthday in 1909.

Laura was an accomplished and talented seamstress. Whether or not times were lean, Laura

made almost all of the children's clothes. As one can imagine, this was no small task. However,

Laura's detractors (most of who were married to her sons) would recount a story to demonstrate her

"extravagance". It seems that, when Laura shopped for material, she would also buy a bolt of

outing flannel and use it for diapers. If the baby did anything more than wet the diaper, Laura

would throw out the diaper and its contents. It would seem that, if one weighs Laura's contribution

to the family as a seamstress against several yards of dirty, discarded flannel, Laura begins to

emerge as a woman ahead of her time...at least in the realm of disposable diapers.

Just after the birth of their thirteenth and last child in 1913, three more events occurred in rapid

succession which radically changed the family chemistry: eldest daughter Pearl married, then eldest

son Orville William married and brought his wife into the household and finally, Will and Laura’s

twelve-year-old son suddenly died. As if in reaction to the changed family configuration and

chemistry, Will, Laura and the family moved to Scotts Bluff in western Nebraska selling the farm

and their homestead to Will's brothers. Will moved the sixteen people of his family into a rather

large rented home at 1815 Avenue C right in the center of the town and took in several boarders as

well. At least one of the boarders, Lucy McCarter, earned her board looking after the Nutter

children.

Will and Laura dabbled in a couple of business ventures; a laundry and a restaurant/cafe called

the "Dew Drop Inn". In both of these establishments, they relied heavily on the labor of the

children who periodically objected and resented their conscription into the family businesses. Son

Perry eventually moved back to North Platte on his own. Son Wellington ("Duke") joined the

United States Navy. Son Banks got a job at the Scotts Bluff Sugar Factory. Finally, there was such

acrimony among the family, Will simply sold the businesses and took the family back home to

Gibbon late in 1920. From that point onwards, Will was wealthy enough to buy back some of his

land from his brothers, lease it out to others, and consider himself retired though he and Laura still

had up to as many as eight children left at home to raise.

Will and Laura Nutter never had a problem providing for their large family. Controlling them

was quite another matter. Members of the extended family and older residents of the Gibbon area

attempt to be discreet, but still describe most of the Nutter boys as "wild, tough and unruly".

All of the local law enforcement officers were familiar with most of the Nutter boys. On at

least one occasion when they were young, the Nutter boys played "Cowboys and Indians" along

the Wood River. Though that may sound benign -- the problem was that they were using real guns

and live ammunition as they played.

Another bit of lore involves a neighbor's windmill which towered over the neighborhood on

the Nebraska plain. Depending on which source one wishes to believe, the Nutter boys would

climb the structure and lash themselves, each other or an unfortunate neighbor child spread-eagle to

the rotating blades.

Many of the boys were proficient boxers and were too often anxious to show off their abilities

in that area. At least two of the brothers earned "golden gloves" status. There are some in the

family that claim Will's oldest daughter, Pearl, also displayed some significant proficiency in

boxing as well and was known to have bested her brothers on occasion.

In the early years of prohibition, Will’s sons began exploring their talents as distillers of

alcohol. One doesn't have to strain one's imagination as to what ensued when the boys combined

consumption of alcohol to excess with a desire to showcase their pugilistic talents.

On several occasions Will Nutter searched for and destroyed several stills his sons had

constructed. Another time, Will spotted what appeared to be a drunken cow in a pasture. He

searched and found that the boys were brewing beer in a trough nearby where the unwitting cow

had recently imbibed.

There survives yet another story regarding the Nutter boys and moonshine -- though it's likely

that it is actually an agglomeration of several stories. It seems the boys were "between stills" and

needed to go to a local man, Jake Vohland, to obtain some illegal alcohol. The boys contrived an

elaborate scheme to simply take the moonshine without paying for it. When the plot went wrong,

some sort of altercation followed and the Nutter boys were arrested and detained for several days

in the local lock-up facility. The jail was unmanned overnight and the boys succeeded in escaping

through a skylight each night during their incarceration and returning before the staff arrived in the

morning. The boys wreaked some kind of havoc each night knowing they would not be blamed.

(After all, everyone knew they were locked up). Judge Wooley heard the charges against the boys

and encouraged them to inform him about illegal stills in the area and who Jake Vohland's regular

customers were. The judge was quick to dismiss the charges when one of the boys mentioned that

Judge Wooley himself was, in fact, one of Vohland's customers. All of this must have made Will

and Laura proud.

As a result of encouragement from their father's sister, Libby Robertson, some of the boys

actually joined up with the Kearney chapter of the Ku Klux Klan for a while -- a curious

association considering they were well aware of their mixed heritage.

For the most part, Will seems to have left it up to his diminutive wife to be the enforcer of

discipline. It has been said that, when Will retired at age 60 (1919), he abdicated much of his

responsibility in guiding and watching over the "children". Perhaps he simply gave up. Instead, he

became a more avid reader and scientist as he grew older, like his father. The Nutter house had no

library, study or office room like his father enjoyed, so Will came up with his own rather unusual

solution. He purchased an old white hearse which he parked in the yard. He stored his books and

papers inside the hearse and spent many hours alone in it. Everyone -- Laura, the children and

even the neighbors -- knew that this was his "office" and that, while he was sitting in the hearse, he

was not to be approached or disturbed.

As the disciplinarian, Laura would win no popularity contests among most of her hell-raising

sons. Her three daughters would also perceive her to have relied too much on their service in the

household. At the same time, the children all revered their father. And why not? After all, Will

could always appear to be "above the fray" -- he could simply retire to the front seat of his

hearse.

Will and Laura worked well together on at least one aspect of their life; dancing. They had met

at a dance and each was very accomplished, particularly in spirited two-steps, jigs and reels.

Laura's frequent pregnancies slowed her down none at all. In fact, she supposedly delivered at

least two of the children the day after a night of kicking up her heels.

By 1930, all of the children had finally moved out of the house except the youngest two. Some

were married and others were out of state, working where they could find work in the great

depression. Early in August, 1933, Will developed digestive problems. A number of folk remedies

were employed all to no avail as his symptoms became more and more acute. The family finally

called in a Doctor Jones on the afternoon of 26 August, but it was too late. Will died at seven

o'clock that same evening of an obstruction in the bowel from a cancerous tumor at the age of 74.

He was buried at the Riverside Cemetery in Gibbon two days later. He had asked that no religious

services be part of his funeral, but someone in the family decided to have the service at the local

Presbyterian Church which was conducted by Reverend Daniel Mergler.

Laura lived only four more years and died of bone cancer in Yuba, California on 26

September, 1937 at the age of 63. However, much had happened during those four years.

Virtually all of her children had moved to the west coast -- only Perry would remain behind in

Nebraska. Laura herself had gone to California with a mind to staying there. In 1935, President

Roosevelt signed a bill creating the "Rural Electrification Project". Indirectly, that would assure the

continued employment and prosperity of the six of Will and Laura's sons who became electrical

lineman as the northwest United States continued to grow.

All of the children of William and Laura Nutter (except Eldore). (Left to right) Perry, Banks,

Everette, Victor, Orville, Wellington, Forrest and Darwin; in front, their sisters; Rose, Pearl

and Muriel. Photo taken in 1946.

The Nutter brothers of William and Laura Nutter who worked as lineman. (Left to right) (at rear);

Orville, Everette, Forrest; (at front) Wellington, Victor and Banks

The Children of William H. Nutter and Laura Myrtle Comstock

William Orville Nutter (1893-1973) - was always known as Orville and formally

switched his first and second name around after reaching his majority. Sometime after 1910, he

was apprenticed as an electrician in Kearney, possibly along with his friend and soon to be brother-

in-law, Coyd Pickrell. He married in 1914 to Myrtle Pearl Reese (1897-1979) and the couple lived

with Orville's parents during the first six years of their marriage -- first in Gibbon, then in Scotts

Bluff, Nebraska. Orville finally got a job with Kearney Power and Light Company and moved

back to North Platte in 1920. Soon after, he got a job as a lineman for the phone company and

moved to Kearney where family lived until about 1936 when they moved to Roseville, California.

He worked for several companies there as an electrician until his retirement. Family members

remember him as a man of great intellect, much like his father and grandfather before him. He and

his wife both died of Alzheimer's Disease during the 1970s. Sadly their three sons and a daughter

did not enjoy the longevity of their parents. Kenneth Bruce Nutter (1914-1971) married twice, had

one son and four grandchildren. Coyd Levain Nutter (1919-1994) had two sons, seven

grandchildren and ten great-grandchildren. Gerald Galen Nutter (1924-1987) had a son and

daughter, four grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren. Jolita Mae Nutter (1934-2001) had

four children with her husband, Robert E. Miller, plus at least 3 grandchildren.

Pearl Lurella Nutter ( 1895-1988) - was the only girl among her parents' first nine

children. As one might expect in a rural farm family, she was disproportionately called upon, in

relation to her brothers, to provide care of her siblings. In fact, at the age of only fourteen or

fifteen, she was left for months with sole responsibility for five of them while her parents and

some of the older brothers went to Texas for an extended time. No one denies that Pearl was the

nurturing influence in the family. By the time she married Coyd John Pickrell (1892-1962) of

Kearney in 1913, she was disinclined to begin a family right away. In fact, it was nearly eleven

years after their marriage that the couple finally had a son who, sadly, was stillborn. Three more

sons were born in the next few years, one died as a child. Pearl's husband Coyd was a lineman and

electrician who earned a good living in Kearney and is credited with training, directly and

indirectly, his six brothers-in-law in that field. They moved to Roseville, California in 1937 and

remained there until 1957 when they moved to San Diego where Coyd died. Pearl returned to

Roseville in 1966 where she lived until the effects of Alzheimer's Disease required she move near

her son and his family in Puyallup, Washington in the 1980s. She died there at the age of 93.

Eldest surviving son Lloyd Gilman Pickrell (1926-2003) died in Kirkland, Arizona after marrying

twice. His second wife, Wanda Nadine Keenan (1925-1999), had been previously married to

Lloyd's uncles Darwin and Everette Nutter. By his first marriage to Madge Meekins, Lloyd had a

son and a daughter. Pearl and Coyd's next son, Garnett Berdine Pickrell (1928-1932), died before

his fifth birthday. Their youngest son, Garland Bennett Pickrell (born 1933), served in the US

Navy and married in 1964 to Kathryn Franzen Bryant. In addition to her children from a previous

marriage, they had a daughter and now, three grandchildren. Garland is retired from Boeing

Aircraft Corporation and lives in Puyallup.

Perry Alden Nutter (1897-1984) - was named for Commodore Matthew Perry and

John Alden, a settler of the Plymouth Colony. He was the only one of his parents' family who

never permanently moved to the west coast. At age 16, Perry began working in the cafeteria and

laundry at the tuberculosis hospital in Kearney, living near the institution with other staff in the

locally famous "Frank House" in the same town. Some years afterwards, he moved with his

parents and the family to Scotts Bluff. Here his father tried his hand at two different businesses: a

restaurant and a laundry. This was unlikely to be coincidental -- Perry's father was probably doing

his best to use whatever expertise Perry had acquired. However, Perry left the family's home in

Scotts Bluff and moved to North Platte, Nebraska where he took employment with the railroad. He

worked with them for the next forty-eight years most of the time as a baggage expressman. Perry's

work required extended periods away from his home base. In the 1930s, when the railroad

contracted to securely transport gold from mining projects in Canada to the Denver Mint, Perry

moved from Nebraska, living in Deadwood and Lead, South Dakota for some time before returning

to Grand Island. After remaining single until nearly his fortieth birthday, this handsome, always

dapper and compact gentleman finally married eighteen-year-old Dorothy Wilke (1918-1990) in

1936. The marriage was far from idyllic and ended in divorce twenty years later, but Perry was an

extraordinarily loving and doting father to the seven children that came along. Even his nephews

and nieces who lived on the west coast remember him fondly calling him a "jewel". He and

Dorothy also lived in Gibbon and St. Paul, Nebraska at times during their marriage. After Perry

retired from the Union Pacific Railroad in 1965, he moved to Puyallup, Washington, to be among

his many siblings in the area, but he missed his more immediate family. Therefore, he returned to

Marquette, Nebraska and eventually moved in with his daughter, Barbara in 1981 when his health

began to deteriorate. He died at the age of 87 from heart disease in 1984. Eldest daughter Sally

Elaine Nutter Roberts (born 1937) lived in California and Colorado before returning to Omaha, had

six children, seven grandchildren and one great-grandchild. Second daughter Betty Lou Nutter

Lyons Ogle Sacco Cannon Niedfelt (born 1939) has nine children from three of her marriages,

several of whom live in Louisiana, Alabama and Florida as do some of the eighteen grandchildren.

Third daughter Barbara Sue Nutter Townsley (born 1941) lives in Grand Island, has a son and a

daughter plus six grandchildren. Eldest son David Perry Nutter (born 1943) is married, lives in

Lincoln, Nebraska and has a daughter. Second son Daniel James Nutter (1945-1999) remained in

Nebraska, married and has two daughters. Youngest daughter Dorothy Delores Nutter Salmon

(born 1948) also lived in California for a while but has returned to Nebraska along with her

husband and two sons. Youngest son John Adrian Nutter (born 1952) is twice divorced, has one

son and has lived variously in Colorado, Anchorage, Alaska and Seattle, Washington.

Wellington Thomas Paine Nutter (1899-1991) - was named for Thomas Paine, the

American political theorist and writer, and George Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, from whom he

also took his lifelong nickname of "Duke". He left the family home in Scotts Bluff to join the US

Navy and, in his own words, "saw the world". He returned to Nebraska in the early 1920s, first to

Kearney, then back to his parents' original home near Gibbon. In 1924, Duke married Wilma Hazel

Dettamore (1904-1969) in Kearney and, with his brother Banks, their wives and children, they

moved to Spring Valley, Iowa, just north of Winterset. The brothers opened a bakery but the

depression took its toll and, after 1930, everyone returned to Gibbon. Afterwards, he and Banks

trained with their brother-in-law, Coyd Pickrell, like their younger brothers Everette and DeForest

had, and all became lineman -- first for the telephone company, then the electric company. After

President Roosevelt signed the Rural Electrification Act in 1934, their expertise was always in

demand. In the late 1930s, Duke and his growing family moved around Ohio and Iowa following

his work. In 1939, he and his family plus Banks and his family relocated to the Tacoma,

Washington area where their sisters had settled earlier. Duke and Wilma raised their family in

Puyallup where they lived the rest of their days. Duke retired from Tacoma City Light Company in

1964. Sadly, he enjoyed his retirement with Wilma for only five years until her death from breast

cancer. Duke stayed on his own for many years and ended up outliving his two eldest sons before

dying himself just before his ninety-second birthday. His eldest son, Wellington Perry (Duke

Junior) Nutter (1925-1980), who was a lineman like his father, married twice and had one son.

Second son, Donald Dean Nutter (1929-1979), died in an auto accident, left a wife, three sons and

a daughter and now has three granddaughters. Elder daughter Doris Wilma Nutter (1929-1929) was

Donald's twin, but was born the day after him and died shortly after birth. Younger daughter Nola

Delores Nutter Bacon (born 1935) has two sons and two grandsons. Youngest son Ronald Lee

Nutter (1937-1996) died of cancer in Shelton, Washington just a month and a half after his wife

died of the same disease. They left three children and two grandchildren.

Lincoln Banks Nutter (1901-1978)

- like his brother Orville, was always known by

his middle name and switched his names around for all legal purposes by the time he was an adult.

He was named for Sir Joseph Banks, a British naturalist and, of course, Abraham Lincoln. He was

married to Isabella Whitcher (1901-1975) in his hometown of Gibbon in 1922 and after his brother

Duke's marriage two years later, the lives of the two brothers and their families parallel for roughly

15 years (see above). Banks and his family moved to Puyallup, Washington in 1939 where he

continued to work as a lineman until his retirement. By the time his wife died of a heart attack in

1975, Banks was already suffering from Parkinson's Disease like his Grandfather Nutter.

Ironically, he died of the disease at virtually the same age as his grandfather. Banks and Isabella's

eldest son, Ebert Bruce Nutter (1922-1947) died with his wife of eighteen months, when a train hit

the car in which they were traveling near Knightston, California, Second son Dewey Ray Nutter

(1927-1989) was married three times. By his first wife, he has three sons and four granddaughters,

all in Washington. By his second wife he had six children, all of whom moved to their mother's

native South Dakota after their parents' divorce. With his third wife he had a daughter and two

grandchildren. Banks and Isabella's eldest daughter Mary Jane Nutter Pierce Johnson (1929-2000)

died in Roseburg, Oregon, and had three sons and three grandchildren from her first husband, two

sons, two daughters and five grandchildren from her second husband. Second daughter

Geraldine

Joanna Nutter Ballard Zachery Brasier Roehr (1932-2004) married four times. She had a daughter,

three grandchildren and a great grandchild from the marriage to her first husband, three children

and six grandchildren with her second

husband and a son with her third husband. Banks and Isabella's third son Gary Lee Nutter (1934-

1995) had a son with his first wife, two daughters with his second wife. Third daughter Belva

Annette Nutter Bennett (born 1936) lives in Tacoma, has one son and four grandchildren. Banks

and Isabella's youngest son William H. Nutter (born 1942) lives in Puyallup, has been married twice

and has three sons and two grandchildren from his first wife.

Ebert Ingersoll Nutter (1902-1914) - was named after Karl Eberth, a German

anatomist and Robert Ingersoll, an American orator known as "the great agnostic". Ebert was

twelve years old when he was kicked in the head by a horse late in the summer of 1914. He

seemed to recover from his injury and was eventually able to return to school. A dubious bit of

folklore survives that a teacher corrected Ebert by smacking him in his head. Whatever the case, a

blood clot became dislodged which eventually caused his death.

Everette Clinton Nutter (1904-1974) - was named after Edward Everette, an

American orator and statesman and George Clinton, another American statesman. He was actually

one of the first of the brothers to be trained by his brother-in-law, Coyd Pickrell, as a lineman. His

father sent him to Kearney to live with the Pickrells in the mid-1920s hoping a trade and steady

work would "tame" him. By 1930, he was working with the Kearney Telephone Company and

eventually got work with the electrification efforts along with his brother, DeForest, in various

localities across the Midwest (principally Ohio and Iowa) late in the 1930s. Everette finally joined

many of his siblings in Washington State sometime before 1941. It has been said that a few of the

Nutter boys made very poor choices for wives. Everette, despite the fact that he waited until his

forty-third birthday to marry first, actually seems to have made two poor choices. First was Lois

Frost McDaniels who was divorced with four daughters when she married Everette in 1947. After

they had a daughter together, Everette began the process of adopting the four girls Lois had. Lois

then abandoned Everette and all but her eldest daughter after the adoptions. After Everette and

Lois divorced in 1951, he released custody of Lois' daughters with her previous husband's parents

(the McDaniels) and put his daughter with Lois (Sandra) in the care of his brother, DeForest and his

wife, Edith, where she flourished. Everette married again, after the death of his youngest brother

Darwin in 1962, to Darwin's widow, Wanda Nadine Keenan (1925-1999) and welcomed the

opportunity to provide for and care for the three young daughters of Darwin with Wanda.

However, Wanda’s interest in yet another family member, Darwin and Everette's nephew Lloyd

Pickrell, contributed to the end of this marriage after a little more than five years. A few years after

he retired, Everette discovered he had lung cancer and moved to Dade City, Florida, to be with his

daughter and her family. He died there on 7 July, 1974. His daughter, Sandra Kay Nutter (1948-

1984) married Illinois native Kenneth Nichol whose work on oil pipelines necessitated frequent

moves around the country. About 1981, she, her husband and their family resettled in Bremerton,

Washington. Sandra drowned in a river rafting accident on the Yakima River at the age of 35. Her

son and oldest daughter live near Chrisman, Illinois and another daughter lives near Colorado

Springs, Colorado. Sandra has six grandchildren.

DeForest Gilman Nutter (1905-1978) - was named for Lee DeForest, an American

inventor and Daniel Colt Gilman, a famous American educator. Though many of his brothers were

proficient boxers, Forest was clearly the best of the brothers in the ring. He was trained as a

lineman by his brother-in-law, Coyd Pickrell, and did line work for the telephone company

throughout most of the Midwest. On New Year’s Day, 1930, Edith Koons (1912-1972) from North

Platte joined him in Missouri Valley, Iowa and they married. Just a little over a year later, their first

and only child, Walter DeForest Nutter, was born at Kearney, Nebraska. The family moved to

Bremerton, Washington late in the 1930s. After raising their own son, in 1951, Forest and Edith

lovingly welcomed into their home Everette's little girl who had been abandoned by her mother.

They raised her until her marriage in 1967. Even though Forest was battling prostate cancer, it was

Edith who died during an afternoon nap in 1972. Forest survived her by six years. Their son

Walter (1931-2005) retired from the United States Postal Service and lived in Bremerton,

Washington.

Victor Hugo Nutter (1907-1974) - was named for the famous French novelist. He

had begun his career as a lineman with the local telephone company in 1928 when Esther Bell

(1912-1998), a local girl, announced she was expecting Victor's child. Since Esther had to have

been only fifteen when conception occurred, her parents offered Victor two choices; marriage or

legal charges for having sex with a minor. When the Bell's pressed the issue, Victor acquiesced.

He and Esther married on 10 September, 1930, eighteen months after the baby's birth. Despite the

inauspicious beginning, the marriage lasted forty-four years and produced three more children. The

family left Arnold, Nebraska in 1941 and settled in Chehalis and then Yelm, Washington, south of

Tacoma in 1951. Victor worked for Puget Sound Power & Light Company for the rest of his career

and died of lung cancer two years after he retired. His wife, Esther survived nearly another quarter

century and died of esophageal cancer at the age of 85. Their only daughter, Doris Jenet Nutter

Halfacre (born 1933) still lives in Tacoma. She had a son (deceased), two daughters, one

grandchild and two great-grandchildren. The eldest son of Victor and Esther was Jack Hugo Nutter

(1929-1965) who died of a cerebral hemorrhage when his only son was 5 years old. That son now

lives in Puyallup and has four sons of his own. The next son was Larry Nutter (1938-2002) who

recently died of lung cancer in Pinehurst, Idaho leaving a daughter and three sons from two of his

three marriages plus a total of four grandchildren. Youngest son Leon Eldore Nutter (1947-1980)

died at 32 from cancer of the brain stem leaving a son and a daughter through whom he has two

grandsons.

Evalina Rosaltha Nutter (1908-2005) - was named for her mulatto grandmother

Evalina Rosaltha Eastman Comstock but she has been known throughout her adult life as Rose Lee.

She was a brilliant student in school and a gifted athlete overshadowing her sister Muriel who

struggled in school. Their mother, Laura, perhaps in a misguided attempt to "equalize" the girls,

downplayed Rose's accomplishments and favored, or appeared to favor, Muriel. As a result, Rose

sought an early exit from her parents' home. Though she married in 1925 at Kearney when she was

just 16, she had made a good match with Royal Lawrence Holmes (1905-1977) and they enjoyed

more than a half century together. They lived in Hastings, Nebraska until they became the first of

the family to move to the Tacoma, Washington area, settling in Parkland in 1936 or 1937. The

Holmes' had four children of whom only two grew to adulthood. In her sixties, Rose's interest in

horseback riding blossomed and she became quite a well-known and expert rider. She enjoyed the

pastime well through her eighties. In her widowhood, Rose outlived her only surviving son and in

1998, she moved to California near her only surviving daughter as Alzheimer's Disease began to

compromise her ability to live on her own. Rose and Roy's elder daughter Joyce Lorine Nutter

(1925-1934) drowned in a sand pit near Gibbon just after her eighth birthday. Their youngest child

was a boy who lived for three days in 1946. Son Larry Dolan Holmes (1933-1999) had three sons,

one daughter and nine grandchildren. Daughter Sherie Lee Holmes Korver Dixon (born 1939) lives

in Shingle Springs, California and is twice widowed with four daughters and five

grandchildren.

Jessie Muriel Nutter (1910-1974) - was known as Merl or Muriel throughout her life

and legally dropped her first name. Muriel was a poor student and was pulled from school early.

Based on the fact that several cases of dyslexia have been found among her descendants, it seems

likely she had the same problem. At home, Muriel worked hard and was often praised and

encouraged by her mother. Under Laura's able tutelage, Muriel became an accomplished

seamstress. If Muriel's sister Rose had ever found any reason to be jealous of Muriel, that quickly

changed once Muriel married Luther Claude Scott (1910-1980) in 1928. Luther was an alcoholic

who worked as a farmhand on local farms. They had a daughter and a son before they moved to

Yuba City, California in 1935. As they moved around that area of California and eventually,

Washington State, Luther's alcoholism and abuse of his wife and children escalated. Unfortunately,

Muriel began drinking too much as well, further taxing the family's already meager resources. In

1948, Muriel finally had had enough and divorced Luther. She moved to Centralia and remarried

to Dewey Emmanuel Lamb (1921-1995) in 1952 with whom she enjoyed comparatively much

more stability. Muriel died from cancer and a thrombosis in Centralia in 1974 just short of her 64th

birthday. Muriel and Luther's youngest daughter, Sharon Kay Scott (1943-1943) lived just a few

hours. Eldest daughter Doris Ilene Scott Dye (born 1929) lives in Olympia. Her son drowned at

the age of 31 leaving a wife and two sons. Doris' daughter has one son. Luther and Muriel's son

Duane Luther Scott (born 1933-2007) was divorced and had two sons, both of whom predeceased

their father..

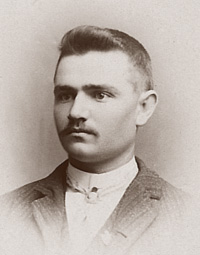

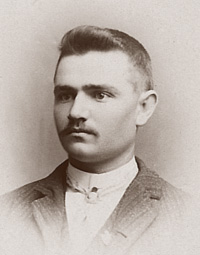

Eldore Emmanuel Nutter (1911-1985) - was strikingly unlike any of his brothers in

appearance, personality and demeanor. This led to gossip in the more extended family that he did

not have the same father as his brothers. Lacking definitive DNA evidence at this point, it is

compelling to note that, whenever photos of Eldore and some of his brothers were presented to

disinterested observers outside the family, along with a picture of William H. Nutter, only Eldore

was consistently selected as William H. Nutter's son. This would seem to indicate that Eldore's

difference in appearance from his siblings arose as a result of his greater resemblance to their

father. Eldore moved to Roseville, California in 1937 with his mother and for years seemed to

move back and forth between there and the other family base near Tacoma, Washington. Perhaps

it was his marriage, in 1947, to Doris I. VandeKamp ( 1913-1988) and his employment with the

Boeing Aircraft Corporation which settled the question, resulting in them settling in Renton,

Washington. He died there in 1985 from stomach cancer. Eldore and Doris had no children.

Darwin Clifford Nutter (1913-1962) was named for his father's hero, English

evolutionist Charles Darwin. Though his name now has more benign implications, in his youth

Darwin's name was a "red flag" to teachers and others who regarded Charles Darwin as a "godless"

influence on society. He married Audrey Angela Bayley (1917-1970) in their hometown of

Gibbon, Nebraska, in 1934 when he was 21 and she was 16 and expecting a baby. Three years

later, Darwin, his wife and two children moved to Roseville, California with his mother and older

brother Eldore. Somewhere along the line, Darwin developed an expertise as an auto body

repairman which insured his regular employment for most of his adult life. Darwin moved back

and forth several times between California and Washington and his marriage to Audrey ended in

divorce in 1946. He married secondly to Wanda Nadine Keenan (1925-1999) in 1951 and they

settled in Yelm, Washington in 1955 after the birth of the first two of their three daughters. Darwin

was sickly as a child. Doctors thought he had rheumatic fever and his brothers would pull him

around in a wagon rather than allow him to walk. Finally, an abscessed tooth was discovered to be

the problem. Once it was pulled, he returned to normal and, like his older brothers, he became a

golden gloves boxing champion. However, the infected tooth left him with a much damaged artery

to his heart which eventually required surgery and for which he required continued treatment. Yet,

his heart problem would not turn out not to be the source of his undoing. Rather, his prolonged

exposure to paints and solvents in his work combined with his heavy cigarette smoking seems to

have resulted in his contracting lung cancer. He died just short of his forty-ninth birthday in 1962.

Darwin's only son, Glen Alden Nutter (born 1935) lives in Allyn, Washington and has been married

three times. His only daughter has one son. Daughter Shirley Joan Nutter McLeod Hebard

McAllister (born 1935) has a son and two daughters. Darwin had three daughters from his second

marriage. The eldest was Judith Carol Nutter Brahun Hughes (1953-2002) who had two daughters

and one grandchild. The next daughter, Terri Lynn Nutter Peterson (born 1954) had three

children and a grandson. Youngest daughter Cheryl Ann Nutter White Bonomi (born 1955) has

three children and one grandchild.

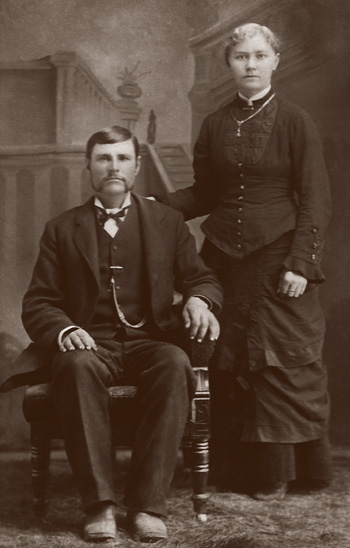

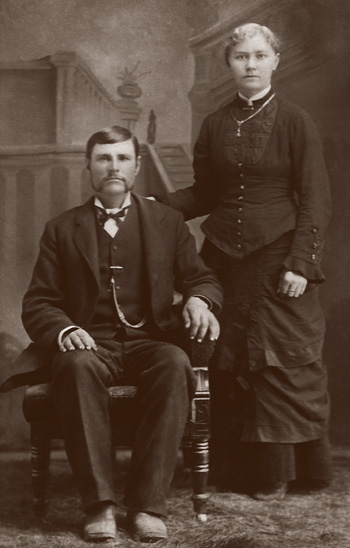

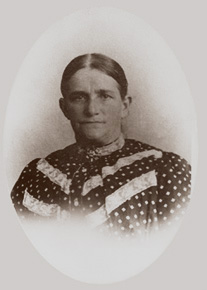

Walter and Ellen Williams

Walter and Ellen Williams

Ellen Nutter, sixth child and eldest surviving daughter of William and Dinah (Ingham) Nutter,

was born during the time they lived among the Mormons near present-day Salt Lake City, Utah.

The family resided at the Sessions Settlement near the growing town of Bountiful when Ellen

arrived on 14 July 1861.

Ellen was just a toddler when she was forgotten...twice...by her family. She was left sleeping

when her parents and older siblings abruptly left the homestead in Nebraska in 1864 fearing an

impending Indian attack and then again, a few months later, as her parents left Liverpool train

station bound for their hometown in England. Of course, Ellen herself had been oblivious to both

the incidents as she was just a toddler. Once her parents recovered from their initial panic, they

were eventually able to see the humor in the occurrence with due deference to Ellen's feelings.

Ellen began school at Old Bethany Presbyterian in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania when her family

returned to the USA. After the family homesteaded in Nebraska, Ellen was schooled first in the

make-shift school in the abandoned railroad shack near Wood River Center, then in the room

above Oliver's Store in the same community after it was renamed "Shelton". She finished school in

the late 1870s and became the first teacher at Bluff Center School nearby.

Either late in 1880 or early in 1881, Ellen met Walter Stanton Williams who was nearly ten