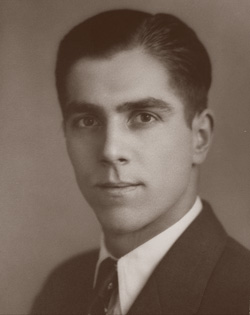

Harry Wagner (circa 1937 - possibly taken at the time of his graduation from the Bradley Institute)

Harry was born in Philadelphia in 1912, 4 years after his parents arrived at Ellis Island from Romania in 1907. Harry had two older sisters, Irene, the oldest, and Helen.

His Dad was a butcher by trade, and soon found a job. Before long, his Dad, following his brother out west, and settled in Great Falls, Montana. When he had saved enough money, he sent for his wife, sister, and children.

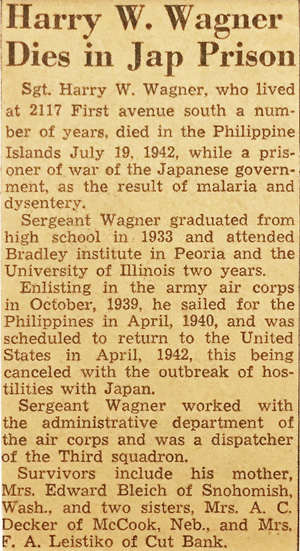

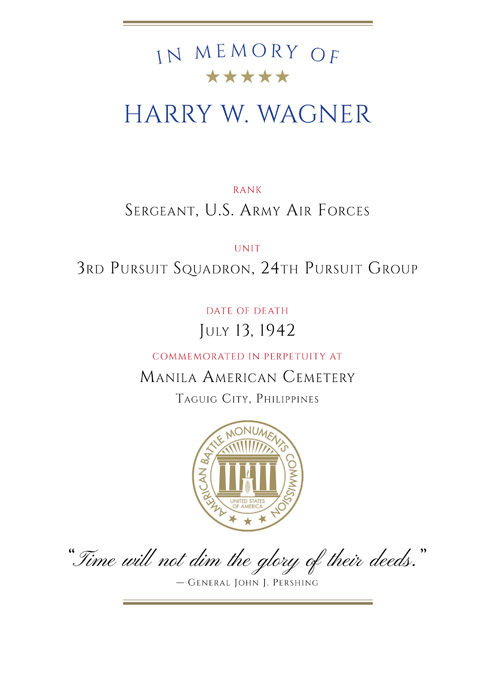

Harry graduated from high school in 1933. From the information in the newspaper clippings below, it seems likely that Harry graduated in 1937 from the Bradley Institute and upon graduation, attended graduate school at the University of Illinois. When World War II broke out in Europe, Harry would have been two years into his graduate studies. From the timing, it also seems likely that Harry anticipated that the U.S. would soon be pulled into the war, as shortly after it started, he joined the Army Air Corp. In April 1940, he sailed for the Philippines, where he worked in the administrative department as a dispatcher for the 3rd Pursuit Squadron, 24th Pursuit Group. He was scheduled to return to the U.S. in April 1942, but the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor in December 1941, and America entered the war. Harry was soon an active participant.

The 3rd was engaged with Japanese fighters from the 2nd day of the war, December 8, 1941. The P-40s that survived the initial Japanese attack were ordered to move to Nichols Field, to provide air defense of the Manila area. On December 10th, without any early warning Radar, the squadron received only a few minutes notice of a second major Japanese air attack focused on Nichols Field and the Naval facilities at Cavite. The remaining pilots prepared to meet the enemy formations. The planes on alert took off to attempt interception however before they could reach the altitude of the attacking Japanese bombers, they were swarmed on by Zeros. Combats broke out across the sky and although outnumbered nearly three to one, the 3d Pursuit pilots did well, downing more Japanese aircraft than they lost. However as they ran out of fuel, they had to break off and land wherever they could find a field. By the end of the day, the strength of the entire 24th Pursuit Group consisted of twenty-two P-40s and eight P-35s. With no supplies or replacements available from the United States, ground crews, with little or no spares for repairing aircraft, used parts which were cannibalized from wrecks. Essentials, such as oil, was reused, with used oil being strained though makeshift filters, and tailwheel tires were stuffed with rags to keep them usable. The aircraft which were flying and engaging the Japanese seemed to have more bullethole patches on the fuselage than original skin. On 12 December, Nichols Field was abandoned and the squadron operated from temporary fields in northern Bataan, and later withdrew on 8 January to Bataan Field, located several miles from the southern tip of the peninsula. Bataan field consisted of a dirt runway, hacked out of the jungle by Army engineers in early 1941 and lengthened after the FEAF was ordered into Bataan. However, it was well camouflaged. It was attacked and strafed daily by the Japanese, however no aircraft were lost on the ground as a result of the attacks. Bataan Field was kept in operation for several months during the Battle of Bataan. The remaining pilots continued operations with the few planes that were left, cannibalizing aircraft wreckage to keep a few planes airborne in the early months of 1942. Many squadron members, unneeded to support the limited number of airplanes fought as infantry.

With the surrender of the United States Army on Bataan, Philippines on 8 April 1942, the remainder of the 24th Pursuit Group withdrew to Mindanao Island and began operating from Del Monte Airfield with whatever aircraft were remaining. Those remaining on Luzon that surrendered to the Japanese were subjected to the Bataan Death March. The last of the group's aircraft were captured or destroyed by enemy forces on or about 1 May 1942. With the collapse of organized United States resistance in the Philippines on 8 May 1942, a few surviving members of the 3d Pursuit Squadron managed to escape from Mindanao to Australia where they were integrated into existing units.

With so few planes left, it is probable that Harry was among the members of the unit who were assigned to fight as infantry. With the surrender in April 1942, Harry and the rest of his unit joined the Bataan 'Death March'. Apparently he was one of the 'lucky' survivors of the march, as the last soldiers arrived in Camp O'Donnell in June 1942. According to the HonorStates.org website, apparently Harry was one of the many of the sick and wounded who were moved from Camp O'Donnell to Cabanatuan Camp 1. The first prisoners were transfered on May 6, 1942. Because the men at Camp 1 started out in worse physical condition than the men from Corregidor who were mainly housed at Camp 3, they succumbed to disease and vitamin deficiency problems faster. By July of 1942, about 1300 men of Camp 1 had died and 32 at Camp 3 passed away.

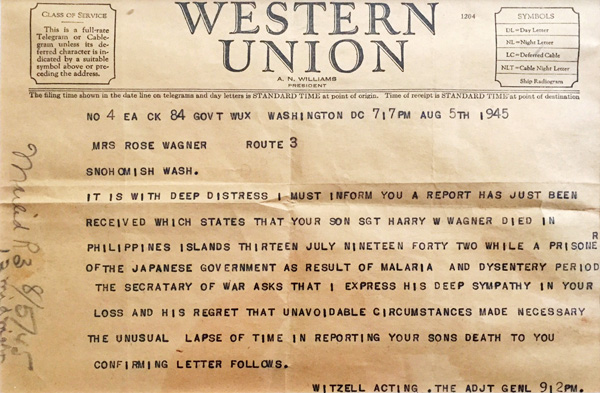

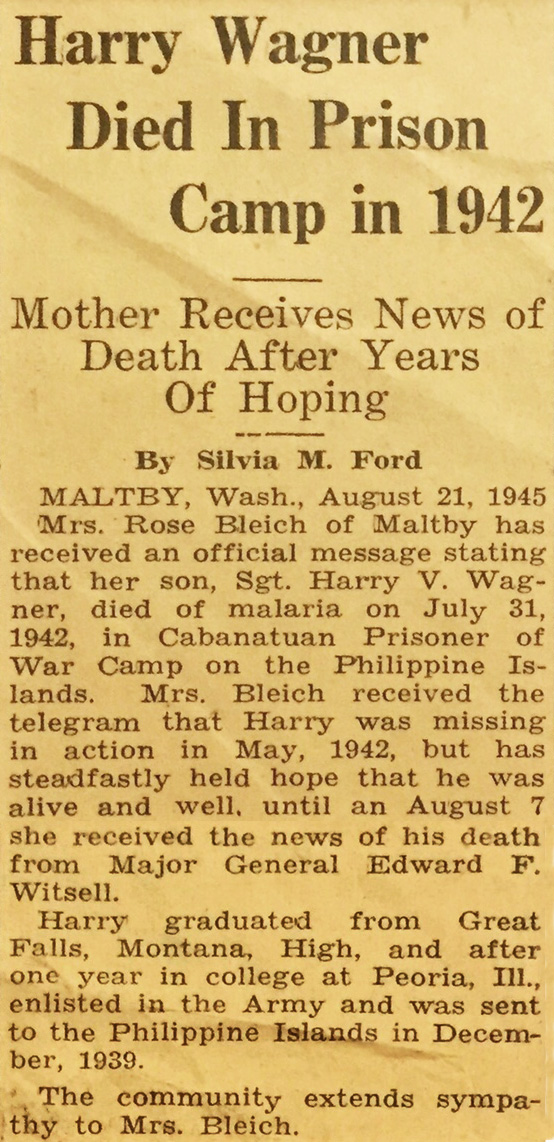

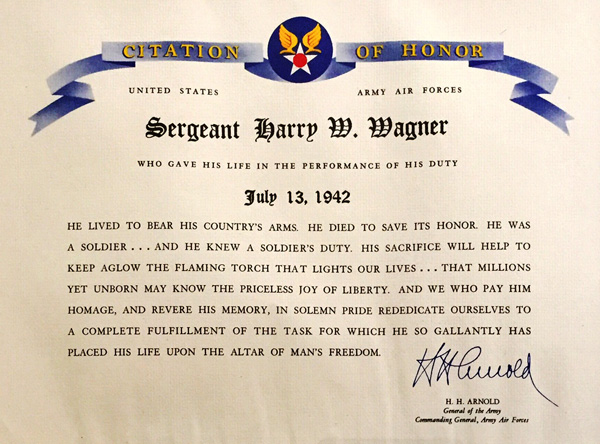

After the Allied forces surrendered to the Japanese in the Philippines, Harry's family knew that Harry was either captured or killed, but they continued to hope that he had survived. Finally, in 1944 the Allied forces invaded the Phillipines, and began occupying the various islands. On January 30, 1945, a daring raid resulted in the rescue of the American prisoners from the camps. (This raid was immortalized by in film. Edward Dmytryk's 1945 film Back to Bataan, starring John Wayne, opens by retelling the story of the raid on the Cabanatuan POW camp, with real life film of the POW survivors. Based on the books The Great Raid on Cabanatuan and Ghost Soldiers, the 2005 John Dahl film The Great Raid focused on the raid intertwined with a love story.) Following this raid, in March-April 1945 the Allied forces occupied the entire island of Cebu. From survivors, the fate of prisoners who died was learned. With this information, the telegram shown below was sent to Harry's mother, then living in Snohomish, WA. It states that Harry died from malaria and dysentery on July 13, 1942. He was posthumously awarded the American Campaign Medal, the World War II Victory Medal, the Prisoner of War Medal, and the Purple Heart.

|

|

|

|

|